The United States treated the enslaved and the American Indians as property. A group joined forces together to take over an abandoned fort and live on their own terms. When the government decided to wipe them out, they had to wage war for their freedom.

GARSON, POWERFUL AND POISED, concealed himself in the trees and brush. The heat was sweltering–then again, it usually was. He had to keep stock still, even while dripping with perspiration and fighting off exhaustion. And he had to be ready to act in case their trap worked.

He and the group hiding alongside him were close enough to the river to hear the water lap against age-old trees whose trunks twisted out of the dark water. Snakes, including the occasional deadly copperhead marked with hourglass patterns, slithered across the ground. The area could be inhospitable, but it comprised a kind of sacred ground.

Garson had once been enslaved. But here he was free.

The men and women who fought alongside him had been beaten and abused; they had watched family members massacred. But here they were free.

They would fight to stay that way.

As Garson gripped his rifle, he had to weigh the possible outcomes that might come from this trap he had set. If the trap worked as expected, they would get the jump on their enemies instead of being the victims of an ambush. On the other hand, it would also mean their lives would change instantly. They would be at war—a war over their existence.

The others by Garson’s side looked to him and waited. They were not after conquest or glory. They had merely claimed the right to survive, a claim that had now led to the most powerful enemies imaginable amassing to wipe them off the face of the earth.

Finally, they could hear rustling in the brush.

TWO YEARS EARLIER, Garson, 30, had reason for concern as he watched British officers scramble in preparation to return to England. Garson was with them inside a state-of-the-art military facility, Prospect Bluff Fort, which rose out of the steamy marshlands of the Apalachicola River in northwestern Florida. It was a sight to behold. At the center of the multiple buildings was an octagonal structure with 12-foot thick walls stretching 25 feet high. That citadel, as it was called, was packed with 10,000 pounds of gunpowder.

Surrounding the main structures was a moat up to 14 feet wide, though they had not filled it with water. “A beautiful and commanding bluff,” a military observer at the time described the fort’s enviable locale, “with the river in front, a creek just below, a swamp in the rear, and a small creek just above, which rendered it difficult to be approached by artillery.” This fort was made to take out armies. But now the commanders were leaving. The place would be decommissioned, fated to gather dust, and slowly fall into ruin.

As the year 1814 wound down, the geographical and moral boundaries of the New World remained in flux. Approximately 35 years after the Revolutionary War, the British still did not fully accept that the Americans had won independence and had decided to test this through military provocation. Escalating clashes against the United States and British-backed troops led to the very first official declaration of war by the United States Congress. Prospect Bluff was in a territory of Florida technically controlled by Spain, and the fort was an ideal location to stage attacks against Georgia and the Mississippi Territory, the vulnerable southern borders of the United States. With its placement on the mouth of the massive river, the fort could launch ships to intercept cargo and military vessels. At the same time, the fort was difficult for any unwelcome adversaries to approach.

The military conflicts between the British and Americans at this time had briefly been known as the Second War of Independence, but now that the conflict had so quickly fizzled out, it ended up with a more prosaic name: the War of 1812. The government back in England lost patience and confidence and recalled the troops.

Garson could see frustration across the faces of the British officials, who had no choice but to follow orders, to give up, pack up, go home. Colonel Edward Nicolls represented the living embodiment of that frustration among those officers. He displayed the toll taken by the attempt to challenge the United States Army and its relentless general of the South, Andrew Jackson. Nicolls had hoped to draw Jackson himself into battle. Now, the Irish-born Nicolls seemed much older than his 35 years, limping and wobbling up and down the parapet of the Fort as he gathered his belongings. He had been severely injured during one of their battles with the United States military, with grapeshot blinding him in his right eye, maiming his leg, leaving him with a head injury, and an even more profound hatred for Jackson, whose principles of aggression he detested.

Their military campaigns had not been without highlights. In the course of building and establishing the Fort, Nicolls, a staunch anti-slavery abolitionist, and his fellow officers had launched a radical maneuver, one that struck the fear of God in many Americans. The southern United States now counted more than a million enslaved individuals, as well as hundreds of thousands of American Indians who were being displaced when not outright slaughtered with the help of the American government. Nicolls and his fellow officers despised the fact that the United States and a powerful man like General Jackson were prospering through slavery and subjugation.

So Nicolls had hatched a plan to weaponize America’s sins against it. He and the other fort’s officers printed what they called their “Proclamation,” which circulated around the region, calling for American Indians and enslaved individuals to come to the Fort. This document was an existential threat to those seizing tribal lands and becoming rich through slave labor–destabilizing those landowners’ very way of life. Fugitives from slavery and embattled American Indians began to come to the Fort, in some cases bringing their families.

The setting could come across as otherworldly. Pines stretched hundreds of feet into the air, creating a canopy that broke the broiling sun into a kaleidoscope of dappled light. It was a remarkable tableau: this spot in the middle of nowhere, not present on any map, transformed into the endpoint of an exodus, with hundreds of disenfranchised people undertaking life-threatening journeys to step across the Fort’s threshold into a new life. A skilled carpenter, Garson fled his enslaver and made it to the Fort.

The idea of a sanctuary for oppressed people was frightening enough in itself for the American military and landowners. Even more alarming to the American South’s ruling class, Nicolls and the British officers began training the new residents of the fort in the use of their weapons, promising they could help Great Britain “make the Americans blush for their more inhuman conduct.” Nicolls guaranteed protection and the opportunity to fight “on the sacred honor of a British officer.” When another British officer visited the Fort to question Nicolls about all of this, threatening Nicolls with severe consequences for overstepping orders, a group of the formerly enslaved men surrounded the visitor until he quietly left, after which he complained that he had feared for his life. Nicolls and the other leaders of the Fort helped transform the refugees into warriors.

But now, with the Fort’s officials being recalled back to England, the region’s enslavers expected that the men, women, and children they considered “runaways” and fugitives would now be duly returned to their “owners.” Still, even now that he had no choice but to leave, Nicolls was not finished with his quest to undermine his enemy. The British officer defied the order to shut the Fort down. Instead, he decided to leave the heavily armed fort in operation in the hands of the group of American Indians and fugitives from slavery living there.

Long ago, Garson had been stripped of free will and choices by people who called themselves his masters. He would have been told he was nothing but a slave, that he was nothing but a piece of property, valued (or devalued) at 700 pesos, and that his life’s only worth was his forced labor.

Deprived of the protection of the British military, Garson could have fled into the wilderness. Instead, he embraced his natural leadership abilities to help guide the residents of the Fort. The British mission may have been finished, but theirs could begin. With their “republic of bandits,” as one observer called it, they were about to send out shockwaves.

THE ISOLATION of the Fort meant little attention was paid to the residents, which gave them time to soul-search about what would come next for them. At first, Colonel Nicolls had hoped that he would soon be able to return to Florida to help them, but after a couple of months, it became clear that his superiors in London would not let that happen. Garson was chosen sergeant major by his fellow Fort residents, who had to maintain a military footing, considering the people of the nearest towns and cities would fume once they discovered what the Fort had become. Other Fort officers were also chosen to serve alongside Garson, including Taboley, a chief from the Choctaws, one of the many tribes that Americans and their allies waged war against to secure control over land and resources. Taboley reflected the interests and goals of the American Indians who continued to move into the Fort, seeking refuge from the American military that terrorized tribal communities.

Garson and his fellow officers had to balance military preparedness with day-to-day life for up to 1,000 residents at any given time. They had a veritable secret city spreading out for miles around the Fort, complete with stone and wood homes, clay huts, a building for worship, and merchant posts, much of which the woods concealed. The residents grew crops and provisions, including green corn and melons, this time to harvest for themselves instead of self-proclaimed masters. Before they left, the British officers had also installed an American merchant more concerned with money than politics, William Hambly, to keep the fort supplies stocked and organized and manage trade. Becoming a quasi-town with its own economy, the community established its own court system and police patrol. Having been left with a fleet of vessels, including two schooners, they found themselves controlling an essential section of the Apalachicola River that ran into the tip of the Southern United States, meaning regional trading and transport would have to go through them.

Garson faced a monumental choice that reached down to his core and tested his commitment to the people who now counted on him. They could view their fortress primarily as a hideout where they could sequester themselves from the rest of the world. The place, after all, had virtually overnight become an unprecedented haven of freedom for people who had been denied any semblance of it for so long. By the very laws of the United States, they and their ancestors had been subjected to unimaginable cruelty and inhumanity since the earliest colonists had come. But Garson was not content to hide away, nor were the other members of the newly self-governing community. They saw their opportunity as coming with a crusade drawn from techniques and priorities instilled in them by Nicolls.

Using the Fort as headquarters, Garson and the leaders dispersed networks of spies, a combination of tribal warriors and former enslaved individuals, across the borders of the United States. They would secretly spread the word of their presence to plantations. Then, from within the properties, enslaved residents would begin cutting down fences and other obstructions.

The Fort’s fighters were coming to liberate the enslaved.

These bold raids were critical in showing that the Fort was not just a hideout for a lucky but relatively small number of people escaping subjugation but also a carrier of principles of freedom. If landowners caught them conspiring, the enslaved individuals inside the plantations could be punished or killed, and the raiders could be enslaved (or re-enslaved).

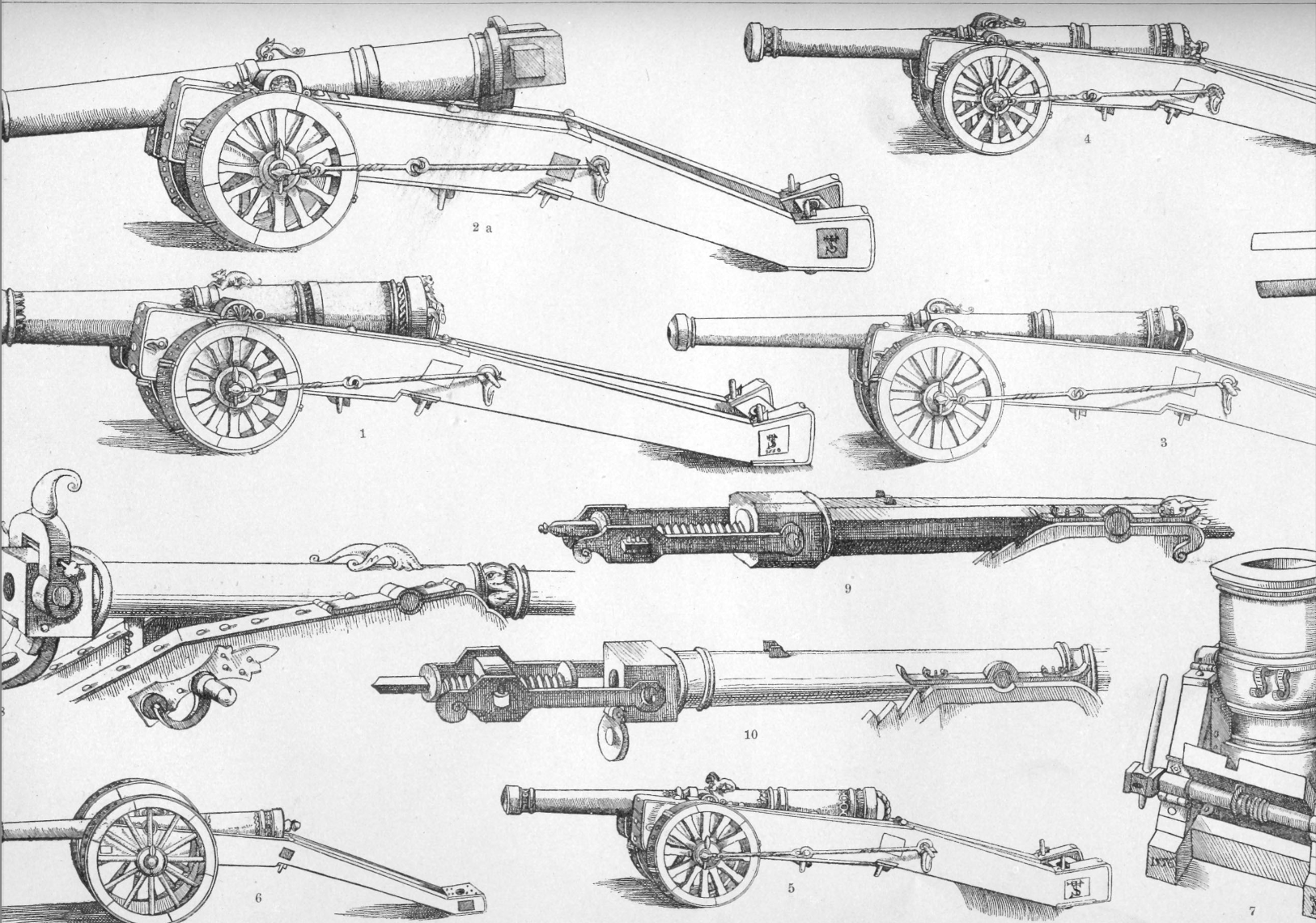

Among the techniques utilized by Garson and his allies, they would fire cannons to signal to the enslaved people on a plantation that a raid was underway. The Fort’s raiding parties would storm the plantations, with enslaved men and women uniting with them to fight against enslavers. The Fort fighters did not hesitate to spill the blood of those who tried to stop their raids. When plantations were located near bodies of water, as in the case of Jekyll Island off of Georgia, Garson and the other leaders would bring their fighters and new fugitives from enslavement onto their vessels and sail off to the Apalachicola and the safety of the Fort.

In some cases, enslaved individuals who had never known anything other than slavery tried to protect plantations. During one of the raids by the Fort’s “outlaws,” one enslaved boy saw signs of an imminent raid and warned his enslaver. The enslaver, thinking he was lying to get out of work, tied the boy to a post and ordered him to be whipped. As one of the enslavers raised his arm to whip him again, he stopped, hearing the sounds of a commotion. The raid had begun. A hatchet from one of the Fort’s tribal raiders struck the enslaver. The terrified boy being whipped was released, now free to join the Fort along with other enslaved men and women freed from the plantation.

In addition to fulfilling a mission for freedom, the raids also provided new residents to the Fort, reinforcing and strengthening the population while adding essential new skill sets–tailors, shoemakers, armorers, shipbuilders–with the newcomers. As word continued to spread about a “Promised Land” in Florida, enslaved individuals who escaped also made their way to Fort, as in the example of one escapee named Charles, who came as far away as Virginia. In some instances, free Blacks–that is, men and women who were not born into slavery or who had previously been enslaved but had been “manumitted” or freed through the legal system–also came from around the nation to the Fort, a remarkable testament to its uniqueness.

As the Fort carried out its dramatic raids, enslavers across the South of the United States descended into fear. Some tried to move enslaved individuals and families into hiding, and in some cases, they abandoned their plantations altogether. One soldier in Georgia during the period described a feeling of “alarm” sweeping through the region, watching as “the inhabitants are flying in all directions.” The Fort was dismissively referred to as “negro fort” and called “the root of an evil” and a “hornet’s nest” filled with “uppity rogues,” “bandits,” “land pirates,” or simply “pirates” since they had their own navy. Those who had crossed paths with residents of the Fort described it as a subversive place that threatened the core values of the United States. “The Negroes are saucy [and] insolent,” came one of these reports. One rumor had it that a woman living at the Fort was so desperate for food that she ate her child and that Choctaws inside were eating “old stinking cowhides.” One observer trembled to see that above the Fort flew “red and bloody flags,” the red flag conveying multiple meanings–their intention not to surrender and their willingness to bleed or shed blood for their cause. One observer who came close to the Fort captured his shock in five words: “They all call themselves free.”

The United States Secretary of Navy wrote with barely restrained outrage that “it appears very extraordinary…so strong a [fort], and with so large a supply of arms, (most of which were perfectly new, and in their cases) ammunition, and every other implement requisite to enable the negroes and Indians to prosecute offensive operations against the United States; in possession of negroes, too, known to be runaways from the United States.” Word reached General Andrew Jackson, the United States military commander for the region. As a significant landowner, enslaver, and scourge to the tribes, General Jackson took personal offense at Garson and his compatriots’ threats to the establishment. He set out to make them public enemies.

GENERAL ANDREW JACKSON, 48, carried his tall frame with an imposing air, the scar across his cheek an outward sign of the hard life of an orphan who fought his way up in the military. “I have very little doubt of the fact,” Jackson vented about the shocking settlement at Prospect Bluff, “that this fort has been established by some villains for the purpose of murder, rapine, and plunder.” Edward Nicolls had represented a vile enough development, not only a British officer trying to undermine American sovereignty but one who had set out to sabotage the institution of slavery. Now, the Fort had developed into something even more portentous. Jackson railed against Garson’s “banditti” and their “secret practices to inveigle negroes from the citizens.”

Maneuvering and manipulation occurred not only on plantations and in smoke-filled back rooms in Tennessee, where Jackson and many of his officers lived, as well as in Washington, but also in London, Madrid, and even as far away as Russia, countries that received word of competing claims about who was responsible for the Fort and the valuable stolen “property” represented by the fugitives. The Fort’s allies back in England, including Colonel Nicolls, sparred with officials to try to send help to the men and women undertaking the venture back in Florida. The American Indian tribes surrounding the region, meanwhile, split between quiet supporters and vocal enemies of the Fort.

General Jackson could take direct military action against the Fort but had to evaluate the risks. For one, the Fort technically stood on Spanish-controlled land, even though it was causing seismic reactions across the United States, which would make it fraught to send in United States troops. Instead, Jackson initiated a chain of events that would cause the Creeks, a tribe allied with the American government, to serve as a surrogate army against the Fort. The Creeks were prominent slaveholders and fumed at what the Fort stood for both in philosophy and practice, which included liberating some of the Creek landowners’ enslaved individuals.

Major William McIntosh, or Tustunnuggee Hutke, was a 39-year-old leader of the Creek faction. McIntosh was pressured to lead an attack on the Fort at Prospect Bluff by Benjamin Hawkins, an Indian agent or liaison with the tribes, on behalf of Jackson. Hawkins appealed to their slaveholding allies’ sense of justice: “Everyone in public service must be prompt and energetic to strike wherever our enemy attempts to injure us.” On a brisk fall day, Major McIntosh marched with, as Hawkins reported, “196 warriors, 20 rounds ammunition, twenty days’ provisions.” Reinforcements joined the Creeks’ formidable detachment to number 400. The instructions from the United States military were clear: “let them take it peacefully if they can, or forcibly if necessary.” The Creeks under McIntosh decided to participate with the inducement of keeping any fugitive slaves who did not have identifiable owners and receiving $50 a head bounty for escapees returned to their enslavers. McIntosh personally owned hundreds of enslaved individuals, and some of them had taken refuge at Prospect Bluff. Jackson and his fellow officers also put pressure on the Seminoles, a significant tribal presence in the area, to capture and return escapees. Chief Bolek, one of the Seminole leaders, found himself caught between betraying his values, which frowned on the institution of slavery, and the potentially deadly wrath of Andrew Jackson.

With McIntosh’s troops on their way with the directive to stop the operation of the Fort at Prospect Bluff, General Jackson no doubt puffed his cigars, his indulgence of choice, as he waited for tidings of the end of the “negro fort,” and restoration of rightful order to their worldview and their economy. “I hope in a few days,” he wrote to Benjamin Hawkins, “to hear of Major McIntosh having captured all the stores and negroes on the Apalachicola.”

But that news did not come.

Map of Fort Prospect Bluff (State Archives of Florida)

GARSON AND HIS FELLOW commanders had the high ground when facing attackers. The bluff on which the fort was built was known in Spanish as La Loma de Buena Vista, or the hill with a good view. Their sentries used this advantage to identify the approach by the Creeks, who, for their part, had given into their racial prejudices toward Blacks by underestimating them. Garson and his troops unleashed careful strategy, not to mention powerful weapons– cannons, howitzers (early machine guns), rifles, and pistols. Above all, they traced the enemy’s movements far better than the enemy could trace theirs. As McIntosh’s troops attempted to breach the walls, a stark gap in motivation between the two sides also crystallized. The inhabitants of the Fort fought for their families, their freedom, and their right to self-determination, while the Creeks fought for profit and political leverage. The residents, derided as “saucy and insolent,” displayed fiery defiance and expertise.

Mary Ashley, a young woman who had fled enslavement along with her husband to come to the Fort, had been learning to operate the cannons, firing across the water at boats bringing warriors. She could now put what she learned into practice. Abraham, another young formerly enslaved resident, embraced the opportunity to learn tactics as Garson commanded the troops.

To the Creeks’ shock, the Fort’s residents repelled the four-hundred-strong attack force under Major McIntosh. The attackers retreated. It was a cause for celebration at the Fort and a message to everyone who overlooked their staying power and seriousness. The Creeks’ exposure to the Fort’s bold fight for fairness and justice against the United States government may well have influenced them because upon their return into United States territory, McIntosh and other Creek chiefs were soon complaining to their liaisons that they needed to be paid better for their services.

Not only did General Jackson and the United States military face a settlement that became stronger with every recruit and true believer within its walls, but they confronted its growing cultural influence beyond its walled boundaries. Jackson bluntly declared the Fort could “endanger the peace of the nation.” The United States Congress saw the Fort as “a post from whence to commit depredations, outrages, and murders, and as a receptacle for fugitive slaves and malefactors... [in] savage, servile, exterminating war against the United States.” In many ways, it was far more terrifying than the brief war with the British that had preceded it. The Congress had to go through proper channels to do something about it.

But Jackson held himself to different rules.

Eschewing the endless political discussions now underway, Jackson decided to take matters into his own hands and send his troops into Florida, an encroachment on Spanish sovereignty that put the whole nation at risk of another war. Many of the region’s powerful landowners supported Jackson. This group included the Innerarity brothers of Mobile and Pensacola, who desperately wanted to restore order among the region’s enslaved population, which allowed them to maintain their enormous wealth. Meanwhile, William Hambly, the storehouse manager inside the Fort, was notorious for siding with whomever presented the most lucrative opportunity. He decided to remove himself from Garson’s “band of rogues” in order to profit from the desperation of wealthy plantation owners.

Plantation owner John Innerarity, hearing in advance of Jackson’s planned assault, wrote to his brother to assure him that the military would destroy the outlaws if they “dare to oppose” them. Jackson was as blase about jurisdictional questions as he was about humanitarian ones. “It ought to be blown up,” he declared, “regardless of the ground it stands on.”

ON JULY 16, 1816, early in the morning, a detachment of sailors from the American Navy floated down the Apalachicola River. The mission, passed down from their regional commander, General Jackson, was simple: kill everyone.

Of course, captured runaways ought to be re-enslaved. They were vital to the economy, after all. But capturing them would not be the priority. The dangers from the Fort and its outlaw inhabitants had become too great to leave anyone alive unnecessarily.

Alexander W. Luffborough, a midshipman, did not hold any particular sway back at his post in New Orleans. In fact, because of health problems, Luffborough had recently given the Navy his resignation papers. But he was persuaded to come on this expedition to Florida, floating down the crooked river with a party of five over whom he was in charge.

Officially, their goal was to locate clean drinking water to bring back to the rest of the fleet. When they spotted a Black man, seemingly alone and unarmed, on the beach amid the orange groves, Alexander knew what to do. He ordered his crew—Robert Maitland, John Burgess, Edward Daniels, and John Lopaz—to steer the gunboat ashore.

Alexander did not want to kill the man–or, to be precise, he did not want to kill him right away. If they captured him, they could extract intelligence on the state of the insurgent Fort to pass on to his superiors. The shore onto which the sailors disembarked was intimidating. The intense summer heat turned to steam that soaked through the clothes and into the skin. Alligators lurked. The ground writhed with snakes and seemed to cave in with each step as though one might fall through the earth.

The five men crept farther into the dark woods, weapons ready. But while they took in every movement, they were also being watched.

CLOAKED BY THE FOREST, Garson’s informants were everywhere. Even the children at the Fort had to learn from a young age how to see while not being seen to protect their settlement, as attempts to spy on and sabotage them escalated. Increasingly, there were also American Indians in the region aligned with but not living at the Fort, a thousand invisible eyes to help spot any intruder with hostile intentions. It evoked the very definition of the river, the Apalachicola—which some said came from the friendly tribe Choctaw’s words apelvchi okla, meaning “helping allies.” This network of spies was vital because their list of enemies was growing exponentially.

One of Garson’s men was sent out alone. That straggler would be conspicuous on shore, appear vulnerable, and be the ultimate bait. As he grew into his role as leader, Garson had proven himself to have steel nerves, but the latest intelligence was alarming enough to rattle him. Indications pointed to an impending assault that could be far larger than the earlier attack by the hostile Creek tribe. Garson had routed those previous attackers, using every unique feature of the Fort to their advantage. The United States military had been pulling the Creeks’ strings behind the scenes, but now General Jackson’s men were putting themselves front and center.

As a strategic commander, Garson played an important role, but the settlement was built with the help and commitment of every man, woman, and child present. They could not dwell on what happened to them before life at the Fort. The message was clear: at the Fort, they defined themselves by their futures, not their pasts. No one ever believed they could come this far, and Garson had no intention of letting anyone steal their future.

So they set their trap and waited.

By the time Garson joined that woodland stakeout, along with the Choctaw chief Taboley, there was soon a rustling in the woods, and their straggler returned. The rustling grew louder and closer as the American naval party made its way toward them. Garson and Taboley hid themselves in the brush. The trap was working.

The American naval squad’s leader, Midshipman Alexander Luffborough, called out to the straggler, ordering him to wait. In addition to Luffborough, five sailors came into view. Garson and Taboley rose from the vegetation. A standoff ensued. The formerly enslaved man and his small group seemed outnumbered by the sailors who had come to capture or kill them. But then more figures, a combination of Black and American Indian, appeared from the woods—by one account, forty of them.

The clash took a turn quickly. Bullets began to fly. Luffborough and two of the men under his command, Maitland and Burgess, were killed instantly. Another member of their gunboat, John Lopaz, ran to the water and swam for his life. Lopaz glanced back long enough to see the last of their party, Edward Daniels, taken prisoner. The first skirmish had seen the “pirates” of the Fort victorious.

Garson knew it was just one battle of a larger war, and with bloodshed had to come regrets for the escalation it would bring. They needed help with whatever might happen next. They sent a trusted messenger to go to the Seminoles, who, up until this point, had been torn between the two sides.

MEANWHILE, THE OFFICER overseeing the American expedition into Florida had yet to learn what had become of the first gunboat in their convoy. Lieutenant Colonel Duncan Clinch, 29, who had thick dark hair and a strong brow, was born during the American Revolution. He came from a military family and intended that his male children continue wearing the uniform. His current mission to take on the Apalachicola Fort had a personal aspect. His family lived in Georgia, where Garson and his Fort had been orchestrating raids to free the enslaved laborers of plantations. Clinch sought not only to do his duty but also to protect the South’s way of life.

Clinch left from Camp Crawford, 100 miles upstream of the Fort in northern Florida, with 116 men, descending the river to rendezvous with a naval contingent that included Midshipman Luffborough. Clinch’s force crossed paths with approximately 150 natives from the Creek tribe led by Major McIntosh, who joined their convoy. McIntosh had already been routed once by Garson’s Prospect Bluff Fort, and he had reason to want to redeem himself.

Clinch’s group halted down the river so the lieutenant could meet with other Creek chiefs, including Kotchahaigo, or Mad Tiger, an enslaver like McIntosh, making them natural adversaries to the Fort. The Creeks wanted their “property” back in the form of enslaved people. But there was a wrinkle here, and it was delicate. General Jackson wanted the Fort destroyed. The Secretary of the Navy added his appeal that the destruction of the Fort was “of great great and manifest importance to the United States.” Clinch could not let the Creeks’ desire to seize escapees get in the way.

On top of that was the issue of invading a sovereign nation’s territory, meaning Clinch had to conduct the operation as quietly as he could. Juggling the many contradictions, Clinch drew up an arrangement by which the tribal troops would be in the vanguard ahead of the Americans and, in the process, capture “every negro” they could find. What they wanted to do with the other American Indian nations—mostly Choctaws, some Seminoles, some Redsticks, a faction of the Creeks who were against the United States—who were abetting the outlaws would be left up to the Creeks. Clinch also promised that if the United States military captured the Fort, they would let the Creeks keep whatever supplies they recovered inside.

The chiefs agreed on these terms and boosted Clinch’s force by more than 500 fighters. One of the United States officers involved in the negotiation commented patronizingly about making arrangements with tribal leaders that “to reason with savage man, before he has acquired any distinct notion of reason, is to effect nothing, and leave him still a savage.” The United States counted on the friendly tribe to help but never granted them respect.

The arrangement with the Creeks had come just in time. Soon after, the Creeks captured the messenger sent by Garson from the Fort to plead with the Seminoles for help– and he had something startling.

The Creeks brought their prisoner to Lieutenant Clinch, who had been on his way on a gunboat toward the Fort. The captured messenger could not hide what he had brought: a scalp. It was a scalp taken from one of the sailors killed in the clash with Luffborough’s gunboat, possibly the scalp of Luffborough himself. (By this point, American Indian and non-Indian soldiers alike had engaged in scalping for hundreds of years.) The prisoner admitted he was transporting the scalp to the Seminoles to show evidence that the United States was turning its might against them and to ask for military support from the Seminoles.

Elsewhere, John Lopaz, the Navy’s sailor from Luffborough’s boat who had escaped Garson’s trap, found his way to another gunboat from the mission and gave his report. He described the ambush by a black “commandant”—Garson— and a Choctaw chief while dozens of others “lay concealed in the bushes.” Lopaz warned his superiors how well organized their opponents had been, seemingly separated into “two divisions,” and how deadly.

Clinch had gained some distinct tactical advantages. He knew Garson’s troops were ready for them, and by detaining the messenger, he might prevent Seminole reinforcements.

Clinch sailed six flat-bottomed boats with a hundred soldiers on each, and the convoy met up with the Creek troops across from the Fort. He ordered them to surround the settlement and clear underbrush sections so they could construct platforms out of wood planks to position their artillery. Some military observers believed the Fort “was sufficiently important to require the presence of General Jackson” himself on the ground. For now, Clinch had to project his superior’s mercilessness. Jackson’s orders regarding the Fort remained easy enough to convey to military personnel: “Destroy it.”

GARSON ORDERED everyone under the Fort’s protection to gather inside the walled-in garrison. The Redsticks—the breakaway faction of the Creeks who fought alongside the Fort—danced around a red pole to the drumming of war music. Some of the others joined this and drank a ceremonial, dark drink. Their cultures had mixed and melded during the time at the Fort. The superstitious among their opponents worried about how drinking the “war physic” might grant them supernatural protection.

From what Garson could gather from intelligence and observe firsthand, they faced an enemy force numbering approximately one thousand. Garson also had to face the impact of one person who had been at the Fort and now was missing: William Hambly. With evidence emerging that Hambly had fled the Fort and betrayed them, Hambly could have been down below with the United States convoys, giving them details of the Fort’s layout and defenses. Meanwhile, some of the Fort’s best warriors happened to be away hunting for food at the time of the siege.

Mary Ashley prepared to operate the cannons with her usual deftness. By this point, they had amassed seven cannons, including four 12-pounders that could blow a hole in a schooner, and thousands of smaller arms distributed with alacrity by Garson’s lieutenants such as young Abraham.

Garson was notified a party was coming holding up a white flag, signifying a desire to talk. He went to meet them inside the gates. The delegation consisted of the chiefs of the Creeks. The Creeks decried the Fort’s murder of the four American sailors from the gunboat. They urged Garson to surrender the Fort and told him that if he did, he would be allowed to survive, albeit returned to slavery. The Fort was surrounded, they said, and he had no way to win.

Garson shouted about the Americans with whom the Creeks had made a devil’s bargain. Americans! From where Garson stood, the real Americans were the ones struggling to achieve the liberty on which the entire idea of the nation had been founded, of which they had been denied. The view from the Fort as darkness fell included the farms the inhabitants had planted, where their corn was thriving. These were their crops, seeded not by the sweat and blood of forced labor but by free men and women for their sustenance. The Fort held the true Americans, brawlers for freedom.

“[I will] sink any American vessels that attempt to pass,” Garson told the Creeks. “[I will] blow up the fort if [I] cannot defend it.”

Garson signaled Mary Ashley. She knew what to do. She raised the bright red flag that announced their position: No Surrender.

The chiefs returned solemnly to the American troops to give their report. Even the enemies of the Fort were awed by the description of Garson’s boldness.

REMARKABLY, the Fort at Prospect Bluff soon found itself triumphing in the largest armed confrontation in history between the United States and people whom it had called its slaves. In the ten days since the first clash on the river, the Fort was virtually unscathed, repelling every attempted barrage from the river and the land. The residents of the Fort had twice as many guns as their assailants and higher caliber ones. Word had also finally reached the Fort’s Seminole allies. Chief Bolek, reluctant to provoke the United States government and Andrew Jackson, realized the military’s assault on Prospect Bluff crossed a line. Bolek decided they would come to Garson’s aid, and the powerful Seminoles were now on the move, marching toward the Apalachicola to help. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Clinch’s troops were running out of food and resources.

However strong their stand, Garson and his fellow leaders knew that if the United States military directed its full power against them, resistance would ultimately require a miracle. However, outside elements could prevent them from getting to that point, particularly considering that General Andrew Jackson had technically invaded another country. Spain could act to stop the unauthorized breach of their borders. If that were to happen, the Fort could continue to grow, build a coalition beyond its bastion, and expand its defenses until no army or navy, not even the United States, would risk challenging them. As it turned out, a fluke moment was about to end these prospects.

Before a catastrophe overtook them, Garson could reflect and worry about the chain of events. He could think back to the trap he had set in the woods when Midshipman Luffborough and the sailors had followed a straggler to where Garson and his fighters were hiding. Had Garson’s ambush been the greatest trap that day? Had the real ploy, perhaps, been by the Americans? After all, it was only weeks earlier that John Innerarity, the powerful enslaver, promised his brother, “If the negroes dare to oppose [the US army] they will doubtless be destroyed.” The Americans wanted the Fort to oppose the invading troops. Luffborough’s small crew had been pawns, sacrifices sent into the Apalachicola to force Garson into violence. Rumors were quickly spread that Garson’s men had tarred and burned the bodies of the Luffborough party. Now the military officials, including Andrew Jackson, could report back to the War Department a flurry of dispatches about “unprovoked and wanton aggression” and “unacceptable hostilities,” announce that the Fort’s “fate was sealed,” and demand a full complement of military power be sent, even if a siege took weeks, months or years to succeed.

Instead came a twist of fate, that fluke overtaking everything else: an American gunboat on the river accidentally heated a cannonball and fired it just “to get rid of it” to prevent it from exploding on the boat. The cannonball ricocheted off a tree near the Fort and happened to strike loose gunpowder. At the time, some women from the Fort opened a magazine door to the armory of the citadel to gather supplies to defend against the siege. A chain reaction of explosions lit fire to hundreds of stored barrels of gunpowder and hundreds of shells, igniting an explosion that took out the entire Fort. Reportedly, people felt the explosion’s “concussion” in Pensacola, nearly 60 miles away. Bodies, including those of babies and children, were strewn everywhere amid the rubble of the once-great fortification. The wooden structures that were their homes and the land that grew crops were burning. Even the American soldiers who wandered the carnage dropped tears at the harrowing scene. However, for slavery devotee Lieutenant Clinch, the tears were not in sympathy for the dead but rather “to acknowledge that the great Ruler of the Universe must have used us as his instruments in chastising the bloodthirsty and murderous wretches that defended the fort.” Another participant in the expedition who witnessed the aftermath expressed “the pleasure he felt at the destruction of the fort” and acknowledged “the gratification it would afford to his government.” Ultimately, 270 fatalities were attributed to the explosion.

The hundreds of Seminole warriors under Chief Bolek, who had been rushing to the Fort and who likely would have overwhelmed the United States troops on the ground, heard what happened while in transit. They had no choice but to turn back. William Hambly, the traitor who had once lived at the Fort, rounded up fugitives from the Fort who survived to profit by returning as many as possible to enslavers on their former plantations.

Garson and Chief Taboley somehow survived the blast, likely having been near each other in one of the sections of the Fort that had sustained less damage. Garson was called the “Black Chief” by some of the Americans who found them, a term meant to mock his alliance with tribes but an inadvertent testament to a community that had succeeded in blending the strengths of multiple cultures in a way the United States had long failed to do.

Garson was blinded in both eyes by the blast. When he was discovered alive, the American and Creek leaders confronted and interrogated him. Ultimately, Garson had one last twist to provide in his astounding journey. He had held the attackers off long enough for several hundred inhabitants of the Fort to slip away into the woods. From having lived as a man in chains meant to be bartered and sold, he had painstakingly transformed into a leader protecting his people; from enslavement on a plantation, he had become one of Andrew Jackson’s greatest nemeses. Garson had ensured that the hundreds of residents of the site were adequately fed, fueled, and ready to fight. He had found a way for as many of them as possible to live another day free, even if he was trading his life for it.

Inside the smoldering, reeking ruins of their Fort, Garson, and Taboley were executed by the Creeks.

MEMBERS OF THE United States military spread false rumors that the residents of the destroyed Fort had a strict rule that they would kill all white people who came near. In reality, the Fort had welcomed William Hamby into its community long before he betrayed them and attempted to re-enslave its residents. After labeling the Fort’s inhabitants as plunderers, the United States military salvaged property from the fort worth what today would be worth more than four million dollars. They took musketry, bayonets, gun flints, carbines, swords, pistols, rifles, and cannon powder. They had promised to share plunder with their Creek allies, though no evidence suggested they did.

Recreation of what once stood at the fort.

The epic events of Prospect Bluff did not end with the explosion two years after the Fort first astonished the nation but constituted part of an approximately five-year ongoing saga. A naval commodore crowed after the Fort was gone that fugitives from enslavement “no longer had a place to fly to.” Yet, in a way, the residents became more dangerous to their enemies once the Fort became ashes. No longer contained in one place, they spread out in a multitude of directions, vowing to avenge the destruction of the Fort and the murder of Garson, now armed with the skills developed in the unique experiences of a Fort that went to war with the United States. The Seminoles welcomed a number of the Fort refugees into their tribes, and the hunt for those survivors by General Jackson factored into the launch of the Seminole Wars. The power and ability of formerly enslaved individuals’ insurgencies challenged their enemies’ racist expectations: “These negroes appeared to me to be far more intelligent than those who are in absolute slavery,” wrote one stunned government official. Garson’s protege Abraham became a groundbreaking leader against the army, seeking to root out Blacks and American Indians. Several new secret cities or settlements arose from those who escaped the Fort, including Mary Ashley. A sense of justice also lived on. One group of survivors of the Fort captured William Hambly and held a trial for him, ultimately restraining themselves from executing him.

Outcomes stemming from the Fort’s saga range from tragedies to triumphs, plus some more complicated to categorize. For example, one of the fugitives from slavery at the Fort was named Fernando; Fernando survived the Fort explosion and was recaptured, threatened with execution until one of Andrew Jackson’s enslaved women fell in love with him. Jackson spared the life of Fernando, who was renamed Polydore, in order for him to marry Jackson’s enslaved woman, but that reprieve also meant Fernando became enslaved again.

Meanwhile, General Jackson built a new American base of operations, Fort Gadsden, where the Fort had stood, turning the locale into a staging ground against the very principles of freedom that blossomed there. Dodging the legal and diplomatic fallout for having carried out military actions on Spanish territory, Jackson and the American government leveraged their campaigns against the Fort to eventually absorb Florida into the United States, reflecting a naval officer’s prediction that the destruction of the fort would wcarry “great and manifest importance” to the nation. Lieutenant Clinch, who led the operation on the river that destroyed the fort, ended up serving in the Georgia House of Representatives and owning thousands of acres in Georgia and Florida, with more than 200 enslaved people working on his land.

Ultimately, on his way to the presidency, Jackson determined to hunt down and wipe out all his enemies who escaped the Fort, though he could not fulfill this vow. A significant group of survivors relocated to the Bahamas. In a small settlement called Nicholls Town, a tribute to their benefactor and friend from England (though with a change in the spelling of his name), they lived in peace and prosperity, trading the murky swamps surrounding the Fort for the blue ocean surf.

Shortly after the fall of the Fort, one of the sailors who had witnessed that siege noted that if the narrative were better known, “it would have resounded from one end of the continent to the other, to the honor of those concerned”–by which he meant honoring the actions of the United States military. The stories of Garson and his fellow inhabitants of the Fort might have achieved legendary status, assuming proportions similar to Scotland’s rebel William Wallace or Rome’s Spartacus. However, the United States government “carefully withheld” details about the Fort’s rise and fall from the public, suppressing official reports about what happened there for years. In the modern era, the site came under the management of the National Park Service. But until 2016, the locale was known only as Fort Gadsden Historic Site, the name of the stronghold Andrew Jackson had built over the ruins to wage war against tribes and enforce slavery. The site recently began to add features that focused on the events surrounding the Fort. A few years ago, Category 5 Hurricane Michael passed through the Florida panhandle and ripped hundreds of trees from their roots, revealing traces of Garson’s Fort, including gun flint and tribal ceramics. The whereabouts of the Fort’s red or “bloody” flag, taken as a souvenir by the United States Navy, are unknown.

DR. LAUREN HENLEY is a historian whose research examines youthfulness, race, gender, religion, and crime.

For all rights inquiries, email team@trulyadventure.us.