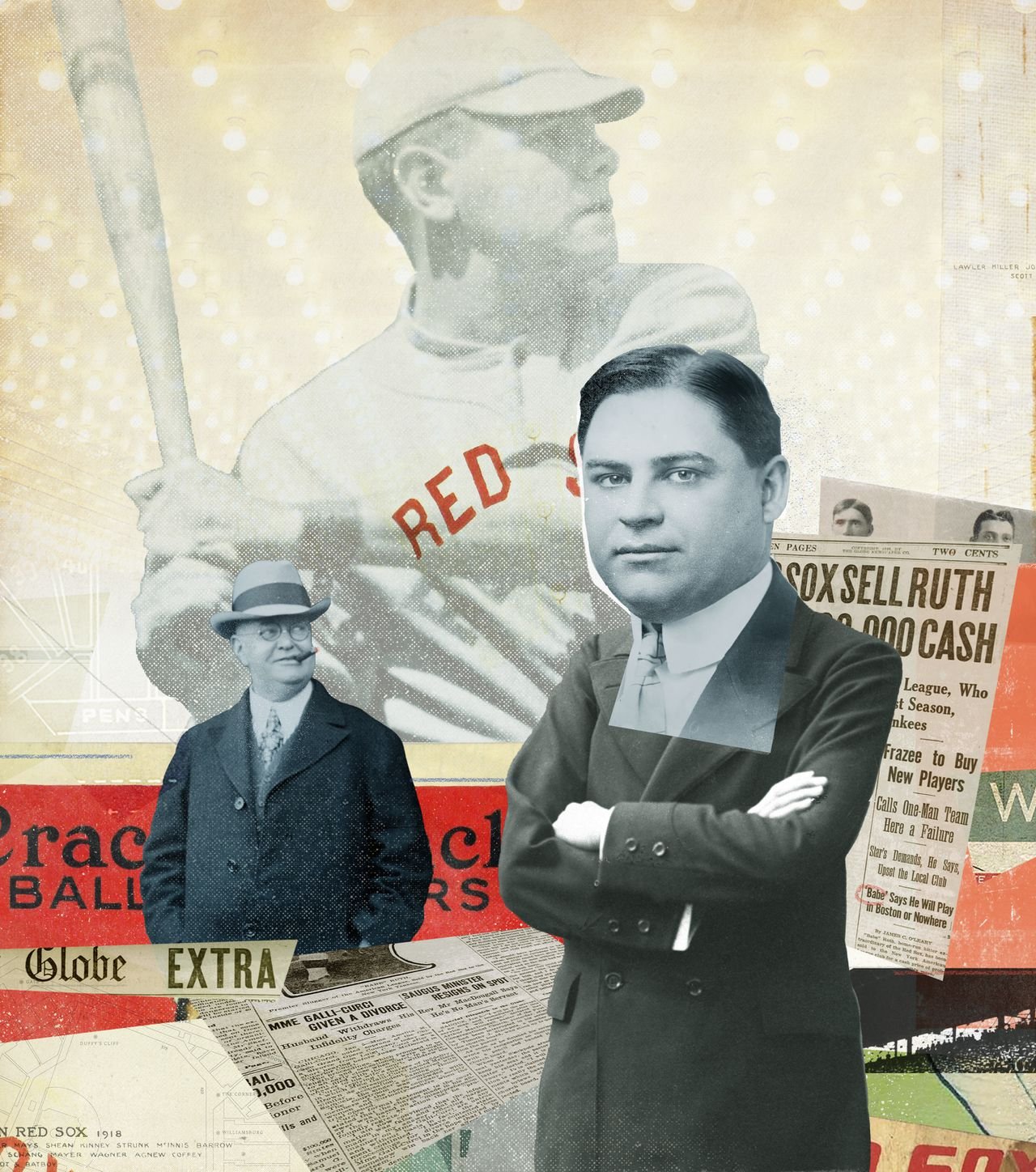

How Broadway showmanship became a sports strategy in the wildest sports deal in history.

…

This story was published in collaboration with The Boston Globe.

Harry Frazee was cornered. It was December 1919, but not even the bright hues of Christmas decorations could bring cheer to his dire situation. As he slumped at the New York City bar staring into another empty glass, the 39-year-old owner of the Boston Red Sox may well have imagined his powerful adversaries closing in behind him.

Frazee, who had earned a reputation as a genius Broadway producer, now faced professional ruin. The experience of recent months had proven that theater — a cutthroat pursuit in its own way — could seem downright civilized by comparison with sports. And if the gamble he had taken on buying the baseball team ended in disaster, it would surely pull down his beloved theatrical enterprises with it.

His latest Broadway show, My Lady Friends, had opened early that month to glowing reviews and big audiences. But Frazee was caught between a malcontent star player weighing down the Sox — the team had landed in sixth place, just one season after winning a World Series title — and a league president intent on ruining him. After buying the Sox in 1916, Frazee had been told, in no uncertain terms, to go away, that he couldn’t succeed, that he’d be destroyed. Now, barely three years later, the nails were being hammered into that coffin.

It was no surprise to also spot on any given night in this gleaming Manhattan barroom Frazee’s drinking companion Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston, co-owner of the New York Yankees. Still in its infancy as a franchise, the Yankees had been plagued by inconsistency, destined to follow up any progress with a few steps backward. That was apparently Frazee’s trajectory, too. With prospects so bleak, the two owners could form a losers' club.

A toast would seem appropriate: To the end of a career. Crushed by big dreams.

And yet it was then, at Frazee’s lowest moment, that the wheels began to turn. Maybe it was the liquid courage — lyricist Irving Caesar once said that Frazee “made more sense drunk than most men do sober.” Or maybe it was simply that old Broadway spirit that told him The show must go on. Either way, Frazee realized he had one more chance to turn the tide and, as it happened, the precise tools he needed to do it.

“Baseball is essentially a show business,” Frazee once observed. “If you have any kind of a production, be it a music show, or a wrestling bout, or a baseball game that people want to see enough to pay money for the privilege, then you are in show business and don’t let anyone tell you different.”

With everything on the line and his back against the wall, Frazee would deploy his unique skills honed in show business to attempt one of the boldest — and sure to be most misunderstood — business deals in sports history. If he had any hope of pulling it off, it would have to be a Broadway blockbuster of sports maneuvers. And it would have to start now.

In the years leading up to his yuletide resolution, Harry Frazee had held onto an almost childlike faith that all his business endeavors would pan out. They always had so far. After dropping out of high school at 16, Frazee had made himself into a well-known theater producer, and was a millionaire by his mid-30s.

Even though Frazee was a fixture in the theater world, he long held dreams of being part of another great American pastime: baseball. As a teenager in Illinois, he tried his hand at playing for the semi-pro Peoria Distillers, and later persuaded a pro ballplayer to invest in one of his shows, earning the man a 1,000 percent return. Frazee had first inquired about buying the Boston Red Sox as early as 1909, and finally purchased the team with a partner in 1916.

There were warning signs, truth be told, right from the beginning. Frazee’s new team was under the thumb of the 52-year-old American League president Ban Johnson. The big-boned, heavy-jowled Johnson stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Frazee at an introductory press conference on December 1, at American League headquarters in Chicago. Johnson said all the right things about his newest owner. But privately he steamed.

Frazee’s cardinal sin had been refusing to kiss Johnson’s ring before his purchase. A Boston Globe story imagined Johnson had expected the previous owner of the Red Sox would have come to him to say, “Please may I sell my ball club, Mr. Johnson?” before daring to hand over the keys. Instead, Frazee had gone directly to the Sox with his $675,000 offer. When it was accepted, he became the first owner in the American League to not first receive Johnson’s blessing — a sin for which Johnson would never forgive him.

Johnson’s dislike struck a personal chord. He and his associates remarked Frazee was “too New York” and groused about the “mystery” of Frazee’s religion. Both comments rang out possible dog whistles to suggest Frazee was Jewish, a canard that may have gained steam in anti-Semitic circles (he was Presbyterian). On top of everything, Frazee, with his silver-headed cane and meticulous style of dress, was “a theatrical man,” hardly a respectable — or particularly masculine — profession in the eyes of titans of the sports world. Johnson made clear, as one reporter soon noted, “that he didn’t consider Frazee the sort of citizen who would be a welcome addition to the baseball family.”

Johnson approached baseball as a gigantic chessboard on which to move living pieces. On that Johnson chessboard, Frazee was an expendable knight, at best, while the baseball players themselves barely warranted status as pawns. Johnson ruled his league with an iron fist, arbitrarily fining players for very minor offenses, a clever way to drain their rising salaries while simultaneously demonstrating his power. His arrogance cowed players, managers, and owners into abiding by his commands.

At the Chicago introduction, Johnson’s welcoming facade hardly fooled the press. A Globe report described it as “cordial” and reported that “Ban made a bit of a fuss over his guests.” Then the article struck an ominous note: “But then it is a common thing to make a fuss over people that are being prepared for the electric chair.”

Back at Fenway Park, Frazee had inherited a bully in the clubhouse who went by the name Babe Ruth. Ruth was the most talented player in baseball, and he knew it. But Frazee, with his experience overseeing Broadway actors, had reason to feel confident he could get the best out of his newest diva.

In 1917, his first season of ownership, Frazee stepped away from many of his theater obligations to focus on the team, which finished second in the league. The next year, through constant hand-holding of their lefthanded pitching star, Frazee and his management team channeled the best of Ruth into a World Series title. But Ruth wanted more money at every turn, and as that money fed his gambling habit, his demands increased. Frazee voluntarily shelled out two separate $1,000 bonuses, but those only whet Ruth’s appetite. As the team prepared for the 1919 season, the slugger made two demands: That he no longer have to pitch, and that he get a raise to $15,000 a season — the equivalent of roughly $250,000 today — more than double his current salary.

Babe Ruth, 1919.

With each new success, the guardrails around Ruth’s ego fell further off. As the 1919 season loomed, without his financial demands met, he stood up the rest of the team, deliberately missing the southbound train to Red Sox spring training in Tampa, Florida. Ruth finally ended up settling for a three-year contract, worth $10,000 a season.

George Ruth’s nickname, Babe, had stuck because he was so young when he signed his first pro contract that the team manager had to be appointed his temporary guardian. But his “Babe” and “Big Bambino” monikers also encapsulated the opinion of many that Ruth acted like a big baby. His all-night drinking benders frustrated everyone on the team. He had a fit at one game when a misunderstanding led to his wife being asked to pay for her own ticket.

At the start of another game, Ruth complained to the umpire that his first four pitches were called balls — he thought two of them were strikes. “Open your eyes and keep them open,” Ruth yelled.

The umpire warned Ruth that he’d better return to the mound or get ejected. “You run me out and I will come in and bust you on the nose,” the slugger replied.

Ruth got ejected, then took a swing at the umpire, as promised — it took several police officers to drag him off the field. The dustup earned Ruth a $100 fine and a 10-game suspension. (“All season Babe has been fussing a lot,” the Globe account noted. “Nothing has seemed to satisfy him.”)

Rather than fighting to be a team player, Ruth was fighting the team. He pitched one game with a swollen and iodine-tinged hand that had been injured in a sparring match with a teammate on the train to Boston. In another incident, Ruth slugged his own manager in the face and quit on the spot, returning to his native Baltimore to sulk. The Red Sox had become a one-man team and that man really didn’t want to be there.

Nor could Ruth’s undeniable talent lift up the team as 1919 got underway, despite his record-breaking 29 home runs over the course of the season. He likely would have had even more, if not for two factors. First, there was Fenway Park’s long right field, which kept balls in the park that would have been homers elsewhere. Second, this was the so-called dead ball era of baseball, when pitchers could still manipulate balls to the detriment of even the league’s most powerful sluggers. The world champion Red Sox finished the season sixth in the American League, 20½ games behind the Chicago White Sox, the team soon to be mired for that same season’s infamous “Black Sox” cheating scandal.

In a perfect encapsulation of Ruth’s modus operandi, the Red Sox still had the chance to win and move up to fifth place on the last day of the season. Long out of contention, they played for pride. But Ruth abandoned the team and left town before the final game. Instead of being in the trenches, he played a lucrative exhibition game in Maryland, pocketing the extra money.

“What’s the use of working your head off to win?” a disgruntled Sox teammate asked a reporter. “The fans don’t seem to care much how the game comes out. . . . All they do is pick up the paper the next morning and see whether Babe made a home run or not. No wonder some of the bunch are getting disheartened.”

Even after Ruth’s stunts inspired fury among the ranks of the team, he was already clamoring for a huge raise for the next season — despite that he had already signed a three-year contract, the duration of which Ruth himself had dictated. He was now treating that agreement, one newspaper noted, as no more than “a scrap of paper.”

As winter blew in, Harry Frazee’s head was in a vise. Crushing him on one side was Ruth, demanding a king’s ransom while simultaneously decimating the culture of the clubhouse. Ruth’s salary would drain their resources and, despite his talent, likely continue to grind their progress to a halt with his untamable ego and plummeting work ethic. The other side of the vise, keeping the squirming Frazee in place, was Ban Johnson.

Johnson’s hatred of Frazee had grown since their introductions in Chicago. The feeling was mutual. Frazee, chafing under Johnson’s control, lobbied for a single baseball commissioner to oversee the American and National leagues, going as far as to approach former US president William Howard Taft to take the job. Incensed by Frazee’s disrespect, Johnson vowed to oust the Sox owner from the league. When the team won the 1918 World Series, Johnson refused to award them their championship medallions.

Johnson worked behind the scenes to poison most of the American League against Frazee and rig the process. The commission set up to arbitrate league disputes, for example, included Johnson himself as well as one of his close friends. The so-called Loyal Five teams — St. Louis, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Detroit, and Washington — allied with Johnson to freeze out the Red Sox, one of the three teams dubbed the Insurrectos.

Frazee was unable even to freely trade for players who might manage to offset the mercurial Ruth. Just as he gauged a cast’s compatibility before they took the Broadway stage, Frazee publicly lamented the loss of “harmony” among the players.

Frazee was set up to fail no matter what he did and, when that inevitable failure arrived, the lost value in the team could wipe him out, undercutting the capital he needed for his theatrical productions. Things weren’t any better at home. His relationship with his wife, Elsie, with whom he shared a teenage son, was on the rocks. When Frazee’s son accompanied him to the theater and the stadium, soaking up his father’s work, he was little aware of his father’s tenuous hold on both.

It was from inside this trap that Frazee found himself that Christmas of 1919 in New York City, where he had his near-constant theater obligations to oversee — this time it was his marriage comedy My Lady Friends. But however much Frazee drank down his sorrows, he had something to prove. “Frazee is not good enough to own any ball club,” Babe Ruth would scoff, “especially one in Boston.”

Especially one in Boston. That rankled. Frazee had to prove he was not some outsider who could be kicked around. “Nobody,” he would say, “is going to run me out of baseball.” He would fight back.

Harry Frazee knew something about being overlooked and underestimated. He started his theater career as a teenage usher, before working his way up to owning multiple theatrical venues. While still an underling, Frazee offered to pay for the right to take a production to another town; the theater owners thought they had the better end of the deal, but Frazee ended up making a small fortune from it.

Now Frazee hatched another plan, this one engineered in the bustling, enterprising New York City that Ban Johnson so despised. To pull it off, he imported lessons of his theater career into a stratagem that stands as one of the boldest and strangest in baseball history, a kind of hybrid game of Broadway Ball.

Ban Johnson, the American League president, in 1921.

Frazee had been an innovator in launching expansive touring performances that could reach as many audiences as possible, and one of his techniques was to tour at approximately the same time as a Broadway run. The attention in the New York media was free advertising to raise interest elsewhere. Frazee even had some shows produce “flying” matinees in New York City suburbs, a tactic he had picked up from West End shows in London. The Broadway cast would be transported out to Long Island and Westchester County for a midday show, and then brought back into the city for the evening performance. No one thought Frazee’s big ideas like these could work, until they did.

Now, Frazee prepared to deploy his first theater mantra in a new venue: When others inch forward, go bigger. Since Johnson had blocked him from trading for players across the majors who might balance out the roles Ruth couldn’t or wouldn’t fulfill, Frazee would do the unthinkable: trade Babe Ruth himself.

Theater producers from the earliest days of commercial stage plays had to toe a fine line to be successful, giving audiences what they wanted without giving them what they anticipated. Frazee possessed a special facility for this, with one contemporary saying, “He made quite a splash because of his propensity to do things opposite from the usual.”

That triggered the next bombshell in his sports maneuver, incorporating his second linchpin Broadway lesson: Do what they don’t expect. Not only would he trade superstar Ruth, he would trade him to a primary regional rival: none other than the New York Yankees. Johnson had jammed trade routes with three-quarters of the league’s teams, so Frazee turned to one of the only trading partners he had left, his drinking buddy Tillinghast Huston.

The Yankees, for their part, tired of playing second fiddle to their stadium-mate Giants, had often been the bottom feeders of the American League. Buoyed by an upturn in 1919, Huston would do anything to grab a player the caliber of Ruth. The secret arrangement represented the most expensive trade of a ballplayer to date: $100,000 to the Red Sox. And obstacles loomed at every turn that could stop it.

Ban Johnson’s fury at the upstart theatrical producer again doing an end run around his authority to engineer a trade was easy to envision. “We do not care what [Johnson] thinks of it,” the Yankees' co-owner Jacob Ruppert proclaimed to the papers, “and do not even consider the idea of him trying to block it.” The comment by the Yankees honcho, no doubt protesting too much, might as well have been, We are terrified what Johnson thinks of it and whether he’s going to block it.

Records are vague about Johnson’s whereabouts during the 1919 Christmas season as the parties scrambled to close the deal. The league boss may have been on vacation, either in Florida or Louisiana. If Johnson was deep in the woods hunting — a favorite hobby of his — the timing would have been part of Frazee’s script. In his current production of My Lady Friends, a Broadway trade paper noted the comedy’s strategy of packing in laughs quickly, making it “a hit before the second act arrived.” Yet another theatrical philosophy from the Frazee arsenal — win before you can lose — applied here, with Johnson offstage during the crucial act.

But that could change in a heartbeat as the newspapers chased rumors, and chief among the sport’s reporters was Paul Shannon of The Boston Post. A Massachusetts native and product of Boston College and Harvard, the 43-year-old reporter was already a legend on the baseball writing scene. One of the charter members of the Baseball Writers' Association of America, Shannon took his job seriously, often arriving hours before game time and settling into a novel while keeping his ear to the ground. The need to know, and be first to know it, meant that Shannon was always looking to break the next Red Sox story. By late 1919, he’d zeroed in on Frazee’s offseason plans and the drama surrounding Ruth.

Playing the press with expert effect had helped Frazee’s rise in theater, boosting his role as a producer into a brand in itself. Frazee leaned on his Broadway identity whenever he faced strife, though at times this caused more complications, with lines blurred between life and stage. With his marriage wobbling, Frazee had begun an affair with actress Elizabeth Nelson, who had graduated from the chorus of productions to leading roles, including in a record-breaking run of a Frazee hit called A Pair of Sixes. A relationship blossomed between producer and actress, leading Frazee to juggle secrets in a dark version of the farcical marriage plot of My Lady Friends. The razzle-dazzle of Broadway — where the next dream always seemed bigger and better — came with personal costs.

In the meantime, with Post reporter Shannon tapped into the worlds of both Frazee and Ruth, the sportswriter soon heard something was afoot in the Red Sox organization. Now he had to chase the story.

Ban Johnson, who had never wavered from his reported comment that “baseball will regret the day that it took Frazee into its councils,” had interfered directly in Frazee trade deals as recently as earlier that year. The clock was ticking for Frazee to tie up his secret trade before Johnson caught on.

Johnson had many levers at his disposal to block the deal if he caught wind of it, but Frazee faced an even bigger threat: Babe Ruth could single-handedly destroy the whole thing in a number of ways. For one, the slugger could drop out of baseball altogether, leaving Frazee in a worse position than before — deprived of a star player without any compensation to show for it. Ruth was already toying with the idea of becoming a boxer. Or maybe he would become a movie star. In fact, as Frazee and the Yankees occupied their respective war rooms, Ruth was in Hollywood trying to stir up movie deals.

The Yankees rushed a delegation to Los Angeles to preempt Ruth from blowing everything up. Team manager Miller Huggins stalked a golf course where Ruth was playing to try to waylay him and lobby for cooperation. At first Ruth dismissed him. The Yankees were anything but a sure thing. Then he quickly turned the conversation to his favorite subject: His paycheck.

Shannon, meanwhile, had begun to pry open the floodgates when he ran an article in the Post under the headline “BABE RUTH IN MARKET FOR TRADE.” The sportswriter started with the shock wave: “Is Big Babe Ruth of the Red Sox to be traded?” Shannon’s language reflected past conversations with Frazee, or at least his inner circle. “There are times when one man becomes even too big for his own club — and a one-man club has never been supreme in baseball.”

To fans who would no doubt read the report in disbelief, Shannon reminded them that “all things are possible in baseball.” Shannon did not indicate any kind of deal in the offing with the Yankees, though he hinted that such a trade would be wise — and in private conversations around town, Shannon appeared to be giving his prediction that the Yankees would be Ruth’s new team. But if Shannon already knew what was underway, the sportswriter held back the bombshell.

With only a matter of time before Shannon went public, Frazee was fending off saboteurs and critics — including in his own circle — who were shocked at the prospect of losing Ruth. No one could be blamed for doubting the viability of the trade. With the volatile Ruth’s response the next shoe to drop, one reporter chasing the twists of the story announced: “The plot thickens!”

But Frazee had another lesson taken directly from the Broadway stage that gave him confidence. It was simple: Performers perform. He had observed plenty of actors walk off the stage in a huff. “They swear they are through with the show, they’ll leave it flat,” Frazee remarked, “but it would take at least two squads of Marines to keep them out of the theater and off the stage.” He had to count on the same about Ruth’s need to pick up his bat. With all the talk of boxing and acting and with an ego the size of California, Ruth at heart was still a ballplayer. Sports and theater alike relied on an inner drive to succeed, but required an external element — the cheering adulation of tens of thousands of spectators — to make them matter. “Ballplayers,” one newspaper reporter wrote at the time, “were more susceptible to flattery than actors.” There was no way Ruth would just walk away from baseball.

Moreover, the audacity of Frazee’s trade in itself may have ironically motivated Ruth to go along with it. It was a personal insult that Frazee would dare to get rid of him. The Yankees delegation, having picked up some rough-and-tumble New Yorker savvy, played this up on the California golf course. As the Yankees manager walked Ruth down the fairway, he told him, Frazee says you were an albatross for the club.

That, and the promise of a hefty raise, was all Ruth needed. He was in, and even dropped an attempt to exploit the rules and demand the money destined for Frazee and the Red Sox. Ruth’s enmity toward Frazee helped seal what Huggins called “the biggest deal ever.”

By the time a red-faced Johnson would have put his rifle down to read the full story in Paul Shannon’s column, the sports world had been transformed.

The Broadway impresario was not content with the splashy headlines in the newspapers on the morning of January 6, 1920. “Red Sox Sell Ruth for $100,000 Cash,” read the Globe front page, “Demon Slugger of American League, Who Made 29 Home Runs Last Season, Goes to New York Yankees.”

Nor was the big price tag paid to the Sox the endgame for Frazee. In the fine print of the deal, Frazee also received a large cash loan, which allowed him to pour capital steadily into both businesses after the turmoil of the Ruth trade cleared. In the days and weeks leading up to the trade, Frazee was busy working on My Lady Friends — not just producing and financing from afar, but personally staging what one trade review called “the best laughing comedy of recent years.” He reimagined My Lady Friends a few years later as the musical No, No, Nanette, the biggest hit of Frazee’s career, giving him a theatrical championship, so to speak, to display next to his World Series title.

Dominoes fell, one after the other, as a result of the Ruth trade. The power and standing of Ban Johnson — “baffled Ban” as sportswriter Shannon called him — never recovered. The spectacle of the trade having happened on his watch exposed the arbitrary and inconsistent limitations Johnson had put on the teams involved. Thanks to Frazee’s expert choreography bridging sports and theater, his nemesis ended up looking unjust and powerless. Though Johnson would remain at his office in Chicago for several years, he accumulated conflicts and public failures of leadership, the Black Sox scandal chief among them. The Yankees brass characterized the trade at the time in a way that equally applied to Frazee, as “an answer to those who would like to drive us out of baseball.”

The next season saw a race of sorts in New York between performances of My Lady Friends on Broadway and home runs by a newly energized Babe Ruth in Yankees pinstripes. Ruth hit a record 54 home runs that year; there wasn’t an entire team in the American League that hit more. He was aided in the feat by a change in the rules that ended the dead ball era, which meant pitchers could no longer alter balls in their favor. The Yankees, essentially a blank slate of a team, also had the freedom and money to engineer every inch of the team’s plans around Ruth, including a highly unusual (considering Ruth’s pitching skill) commitment to him that he would not have to take the mound. With the Yankees able to maximize Ruth’s batting talents in a way no other team could have done, the Insurrectos that Johnson had attempted to crush now had power.

With value restored to their disrespected corner of the league, when Frazee went to sell the Red Sox three years later, he received $1.25 million, an incredible return on the $675,000 purchase price in fewer than eight years.

Harry Frazee, left, and Frank Chance, owner and manager of the Boston Red Sox respectively, huddle at Yankee Stadium in 1923.

History would go on to judge Frazee harshly for selling baseball’s best player. But the notion that the Red Sox would have succeeded the way the Yankees did is far from certain. The Yankees remade themselves from top to bottom for Ruth, even as the personal motivation created by the trade fueled Ruth’s success so soon after he had flirted with leaving baseball altogether. In other words, without the Babe Ruth trade, Babe Ruth may well never have been a baseball demigod. The Yankees actually built Yankee Stadium to highlight Ruth’s strengths, engineering the short porch in right field to maximize his home runs, likely the first time in the history of professional sports that a stadium was tailored to one player. Six months after christening that stadium, the Yankees won their first of many World Series.

For all his talent and bravado, even Ruth himself could not know the heights he would reach — if he did, he would never have seriously considered stepping away from the game. Harry Frazee couldn’t predict the future either. But what he did know at the time of the trade was that Ban Johnson, and Ruth himself, had made it impossible for the slugger to remain in Boston. So Harry Frazee, far from a bumbling pawn, did what he did best: put together a deal with all the drama and flair of one of his Broadway hits. In less than a decade of owning the Red Sox, Frazee had won a World Series, given the slip to enemies bent on destroying him, nearly doubled his investment, and proved that if all the world was a stage, baseball could be one hell of a show.

DAVID K. THOMSON is an assistant professor of history at Sacred Heart University in Connecticut.

For all rights inquiries, email team@trulyadventure.us.