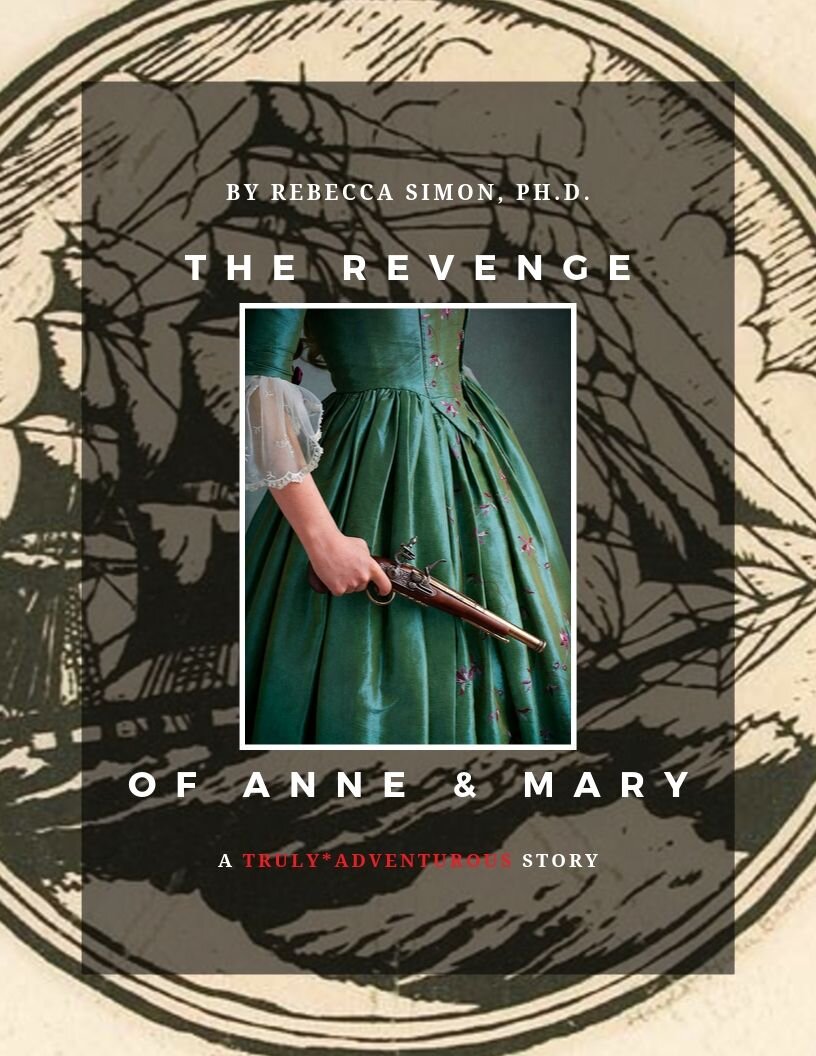

Two women take to the sea and become the most feared pirates in the world. Rare archival material brings to life the most authoritative narrative of history’s boldest pair of renegades.

Summer 1720

Anne Bonny made an unforgettable impression from the bow of the pirate ship, Revenge. Beautiful with fiery red hair that matched her temperament, she’d patrol the ship wearing a jacket and trousers, with a handkerchief tied around her head. Though forced to disguise herself as a man to lead the life she wanted, Anne proved herself to be just as skilled and ruthless as any pirate.

One of the crew’s newer recruits was a man named Mark Read. His backstory remained murky beyond the fact that he had previously served as a soldier and only more recently a sailor. His seamanship skills were practically unmatched by anyone onboard. During their first successful attack on another ship, Read held nothing back, fighting without fear.

Anne found herself taken with Read. His bravery and fighting skills deepened an insatiable attraction. She worked near him and engaged in witty conversation at every opportunity. Finally, one day, Anne saw her chance to express her feelings.

Read went into the storeroom alone to gather some supplies. Anne followed him and shut the storeroom door behind her. Anne unbuttoned her shirt, revealing her breasts to Read to show him she was a woman, and declared her love for him. Not missing a beat, Read unbuttoned his shirt and revealed a pair of breasts to Anne. Mark Read was Mary Read, the star sailor explained, also posing as a man in order to serve at sea. Their passionate, secret love affair began then and there. The appropriately named Revenge became the setting of their romance, their legend, and their downfalls. The particular forms of revenge sought by Anne and Mary were against a world that manipulated them based on their gender, against the men who had failed them, and against societal rules that had tried to cheat them out of their potential.

Two Years Earlier

Anne first got a taste for the pirate life when she met a man named James Bonny, a sailor and part-time plunderer. At the age of sixteen, she married James against her father’s wishes. She and James set sail and pirated at sea for several years until finally settling in Nassau, New Providence (part of present-day Bahamas) in 1718. Nassau was a curious place to choose; at the time, it was known to be the most notorious pirate haven in the Atlantic Ocean. This did not deter a young woman who had been through as many travails as Anne.

Anne was born in Ireland, the daughter of a married attorney and his servant. When her mother died, her father moved to London to avoid the family of his estranged wife and chose to raise Anne as his son. Even though his neighbors knew the child to be illegitimate, it was socially acceptable for a boy to be provided for out of wedlock, while illegitimate girls were often tossed aside. This set a precedent for Anne’s anger toward the limitations imposed on her because of gender. Her father’s wife soon discovered the truth about the secret child and cut them off from her family’s allowance. In order to limit his disgrace, her father moved them both to South Carolina to open up a new practice. Her gender presentation was flipped again when she was sent to work as a servant girl around the age of thirteen. Anne was known to be hot-tempered and was even rumored to have stabbed a boy who insulted her, and her employment was soon terminated.

The relationship between Anne and James Bonny began to deteriorate not long after they arrived as husband-and-wife in Nassau in 1718. James Bonny seemed eager to abandon his piratical ways, to his wife’s dissatisfaction. The pirate ship was where Anne felt the freest and most powerful. Pirates were beholden to no laws. Class status didn’t exist on a pirate ship; her bravado and skills counted the most. The fact that her husband no longer wished to live that life turned her stomach.

Taking refuge in taverns, Anne sought out the intimate company of sailors and other pirates. One of those pirates was a captain named Jack Rackham, who stopped in Nassau to refresh his supplies and crew. Standing at medium height with fair hair, he donned a coat decked out with ribbons and brass buttons and wore silk stockings, despite the tropical heat, as well as buckled shoes that often adorned the wealthy. Enamored by his fine way of speaking and expensive attire — the sources of his nickname “Calico Jack” — as well as his rank and reputation in piracy, Bonny initiated a sexual relationship. This was likely further fueled by the fact that her husband James had started working for Woodes Rogers, governor of the Bahamas and a former pirate turned pirate-hunter. To pirates, Rogers was the Antichrist. Anne would rather die than stay with her turncoat husband.

Rackham fell in love with Anne and approached James to grant her a divorce. James refused. Anne pleaded with James to allow a “wife sale,” in which he could sell her to another prospective husband. Even the possibility of making money didn’t budge him. She even appealed to Governor Woodes Rogers himself, who refused to recognize the custom and threatened to whip and imprison Anne for her “loose behavior.”

Anne ran away with Rackham in the night and they married on the ship. It was not uncommon for married people to remarry at sea without a divorce or annulment, since the sanctity of land-based marriages ended at the water’s edge. Oftentimes it was the captain who would facilitate the wedding — by which custom the resourceful Rackham may have officiated his own marriage. Rackham was later heard saying, “My methods of courting a woman or taking a ship were similar — no time wasted, straight up alongside, every gun brought to play and the prize boarded.” No doubt keeping the marriage secret among the crew was expedient, leaving Anne a reason to continue to dress as a man.

James Bonny was so humiliated and furious at this turn of events that he threw himself deeper into his work as a pirate hunter. Chasing pirates was dangerous business, but James was driven by a virtually Shakespearean motivation — payback against his estranged wife and her new husband. Safe to say, James was the only pirate hunter ever to chase his pirate wife across the seas with the intent to kill.

Anne and Rackham began their joint pirating career in earnest on August 22, 1720 when they captured one of the largest and fastest vessels in the Bahamas thanks to its long hull (the watertight underside of the ship), which increased the ship’s stability and wind-resistance: the William, which Rackham promptly renamed the Revenge. Once on board their new ship with a refreshed crew that contained several new members, the pirate power couple set sail. It was on this voyage that Anne fell hard for the intriguing sailor named “Mark” — really Mary — Read.

Their sexual relationship that began in a dark, crowded storeroom would not remain secret from the captain for long. Rackham noticed how much time Anne and Read spent with each other alone. Their laughter and playful physical contact incensed Rackham. One night he walked quietly below deck to the berths where he found Read asleep. One theory is that he found Anne in bed with Read, both partially unclothed. Then he pressed the blade of his knife against Read’s throat, waking his crew member with a terrifying start.

Mary Read had first arrived in Nassau around the same time as Anne. Like Anne, Mary was also born illegitimate, and, most strikingly, also raised as a boy. Born and raised in England, she was the result of an affair her mother had with a sailor shortly after being widowed. When Mary’s half-brother from her mother’s previous marriage died, Mary was disguised as the legitimate son so they could continue to receive monetary support from her paternal family. She did not even know she was a girl until she was thirteen years old, when she was placed into servitude. Mary soon ran away from her employer, resumed a male presentation and began calling herself Mark.

Mary had grown into a tall woman with high cheekbones and dark, curly hair, which could easily be concealed by tying it into a ponytail, a male hairstyle at the time. Mary crossed the English Channel to join the British army in Flanders, where she fell for a soldier. They married in secret and later opened an inn together, but her husband died of illness. Overwhelmed by grief, Mary disguised herself as Mark yet again and rejoined the army. However, her depression set her back and she was soon discharged. Refusing to go back to a life of few opportunities, destitution, and servitude, she fostered her male identity and joined a series of maritime crews before ending up aboard the newly-christened Revenge.

Now with a knife to her throat in her berth, Mary faced the fury of her captain over her relationship with Anne Bonny. Rackham accused Read of illicit behavior and lust for Anne. He said he would kill Read for his indiscretions. Once again Read had to expose her secret. She undid her shirt and revealed herself to Rackham. He was so shocked that he fell backward.

At first, Rackham’s suspicions of an affair were eased. After all, they were both women. But Rackham soon recognized the truth that their relationship went far beyond friendship. Freshly inflamed by jealousy, he threatened to kill them both. He said he would spare their lives and let them continue their relationship on one condition: he had to be included into their romance. They would be a threesome. The women agreed, and both became wives of Captain “Calico” Jack Rackham.

August 1720

After agreeing to Rackham’s conditions, the two women made an astounding choice: they made the decision to stop hiding genders. During the “Golden Age of Piracy,” a period in which Atlantic piracy was at its height spanning 1690 to 1726, the idea of women working at sea would have been unusual in itself. The notion of female pirates? Abhorrent. The pairing of two female pirates defied law, society, and culture in every way imaginable.

Knowing that they had the captain on their side, Anne and Mary decided that sailors’ rules be damned. They cast off their disguises and threatened to kill anyone who would dare cross them. They would go back to men’s attire when it suited them, or wear men’s garments in a way that did not hide the fact they were women. According to the testimony of a onetime hostage on their ship, the women carried a sword and pistol in each hand, and in battle they would bare their breasts for all to see and curse louder than anyone else. Tales of the two women exploded throughout the Caribbean, the North American colonies, and England. Not just female pirates, but women who exposed themselves as they fought! The Revenge met with wild success: After stealing their first ship in August 1720, they captured several more in quick succession.

James Bonny seethed as he sought out the woman who was still legally his wife, wrecking his name as quickly as she wrecked ships. He chased rumors of Anne’s whereabouts until he came upon the ship of a notorious pirate, Captain Charles Vane. Vane had the reputation of being one of the most violent outlaws in this region and his capture would yield a fortune. With this reward, James could afford a more powerful ship and crew to recapture his wife and kill Rackham. His battle against Charles Vane was vicious. James was killed. Anne was probably as sad as anyone who heard of his demise, for no doubt she would have wanted the sword that ran through him to be her own.

September 1720

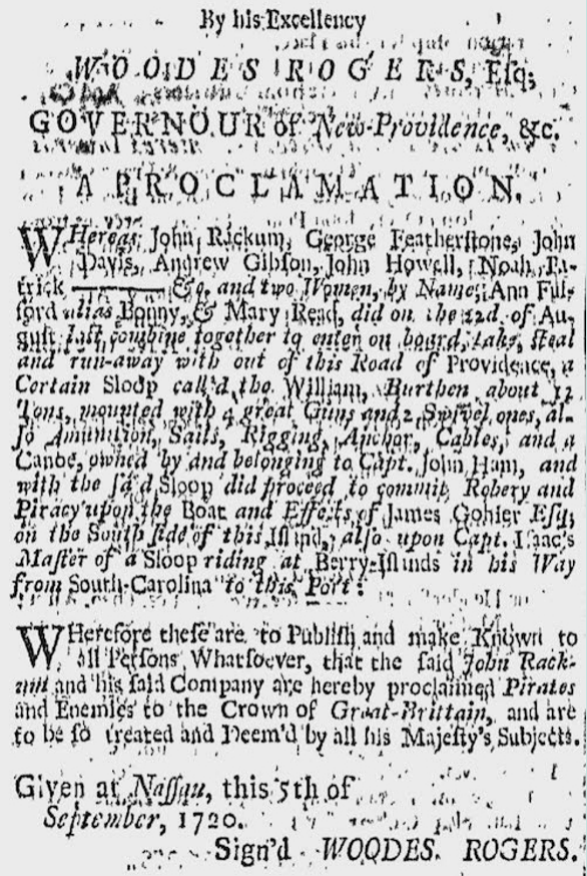

News continued to circulate about the scandalous marauders onboard the Revenge. Woodes Rogers, increasingly nemesis to all pirate-kind, enlisted privateers to hunt them down. He also sent a reissue of the Proclamation of the Effectual Suppression of Piracy to several prominent North American newspapers. The Proclamation promised to pardon pirates of all of their crimes if they turned themselves in and named their accomplices. This Proclamation had been issued several times by this point, but most pirates, though cutthroat, were loyal to their creed, refusing to give each other up. As a final attempt to seek their capture, Rogers issued his own proclamation and made a point to highlight the female pirates, Anne Bonny and Mary Read, to garner attention:

Whereas John Rackum[sic]…and two Women, by Name, Anne Bonny & Mary Read, did on the 22nd of August last combine together to enter on board, take, steal, and run-away with out of this Road of Providence, a Certain Sloop call’d The William…Wherefore these are to Publish and make Known to all Persons Whatsoever, that the said John Rackum and his said Company are hereby proclaimed Pirates and Enemies to the Crown of Great-Brittain, and are to be so treated and Deem’d by all his Majesty’s Subjects.

Anne and Mary were now international outlaws.

On September 3, 1720, Rackham, Anne and Mary successfully robbed and captured a team of seven fishing boats off the coast of Harbor Island in the Bahamas. They attacked without mercy. After a bloody fight, the fishermen lost their boats, fish, fishing tackles worth ten pounds in Jamaican currency, and all of their wares — destroying not only their goods, but their livelihoods.

A month later, on October 1, the pirates sailed toward Hispaniola where they targeted two merchant ships about three leagues off the coast of the island. Anne and Mary led the charge and immediately fired their pistols at the merchants. Within minutes the merchant ship was theirs. The pirates stole all of the cargo valued at over 1,000 British pounds, the equivalent of $183,000 (US currency) today.

Such a large prize gave Rackham confidence to the point of foolhardiness. He redoubled their efforts and commanded his crew to attack any ship that crossed their path. Anne and Mary were alarmed. Pirates were superstitious about luck and they knew that their successes could give way to disaster in a heartbeat. They cautioned Rackham to be less hasty, but to no avail. Above all else, Anne and Mary were loyal to their captain and each other, so they steeled themselves and committed to their cause.

On October 19 off the coast of Port Maria Bay, Jamaica, they captured another merchant ship captained by Thomas Spenlow. Rackham used trickery to lure the ship close, hailing it with the Union Jack, or British flag, as a disguise and shouting, “We are Englishman! Come on board and have some punch.” Encouraged and relieved by this salutation, Spenlow agreed to join Rackham’s vessel, leading his men right into a trap.

Anne and Mary killed several of the merchantmen on board. They chose to spare Spenlow’s life and allowed him and a few of his crewmen to sail away in a small boat. Then the pirates changed their minds, ending up chasing after Spenlow and taking him as a prisoner, likely to use as ransom at an opportune time. The attack yielded about twenty Jamaican pounds worth of goods, roughly $2,500 in current US value.

The next day Rackham sailed his ship around the coast of Jamaica until they came upon Dry Harbor Bay. There they captured a merchant ship called the Mary. This attack yielded three hundred Jamaican pounds worth of goods (roughly $37,000 in today’s US dollars) for the pirates. Later, the captain of the Mary described his astonishment that the women seemed to be pirates of their own free will.

By this point, Jack Rackham, Anne Bonny, and Mary Read were feared by everyone at sea. It only took months for this trio join the ranks of the most infamous pirates in world history. Word of their exploits reached the governor of Jamaica, Sir Nicholas Lawes, who already harbored intense hatred toward pirates. Determined to bring them down, he commissioned privateers, roles similar to pirates but sanctioned by the government to attack enemy ships, to capture the Revenge. A pirate hunter named Jonathan Barnet soon caught up to Rackham’s ship.

An experienced and hardened seaman, Captain Barnet took his role as a pirate hunter seriously, applying little mercy to his quarry. Barnet had been active as a privateer for about five years, since the first time the governor of Jamaica, Archibald Hamilton, deployed him to hunt pirates. As a privateer, Barnet learned pirates’ methods and hideouts. Since his commission paid him by allowing him to keep any plundered goods, he recognized which goods were most popular to steal and therefore knew which shipping lanes to pursue. Barnet was so shrewd and determined as a privateer, that he found evidence that Hamilton secretly traded with pirates. Barnet provided proof of Hamilton’s misdeeds to the Admiralty Court and subsequently had his own patron removed as governor — no one associated with pirates was safe from Barnet.

Using his expertise and cunning as a pirate hunter, Barnet tracked down Rackham’s ship. He was able to extract gossip from sailors that Captain Rackham had holed up off the coast of Negril’s Bay in Jamaica. With a second armed ship helmed by his colleague, Captain Bonnevie, Captain Barnet set sail toward Negril’s Bay.

The bay was not a far journey from Port Royal and the captains reached it in just a few hours. From a safe distance they spotted a large sloop lying at anchor in a small cove just off the shore. The location of the ship was suspicious as a spot for a vessel to make anchor. The coast was a four-mile stretch of sand and swamp and a hotbed for mosquitos. Only a pirate would be desperate enough to take shelter in such a place. Barnet decided that the best time to attack would be in the dark. They anchored their ships just out of sight and settled down to wait.

In the meantime, Anne and Mary were at their wits’ ends with Rackham. He was making rash decisions about whom to chase and where. He wanted to head to sea-lanes populated with merchant ships, which increased their risks of capture. He would not listen to reason and became reckless with his winnings, especially their stolen alcohol. Their enemies only had to outsmart them once, or get lucky, and they’d be wiped out.

To Rackham’s eyes, Negril Bay was a good spot to hide. No one would want to sail into this pit. What place was better to hold a raucous celebration? Dizzy with success from their most recent plunder, Rackham and his crew began drinking all of the liquor they stole. The only two pirates not to engage in the party were Anne Bonny and Mary Read. In their exasperation they picked up their weapons and began their watch.

As light faded into evening, Captain Barnet hoisted his anchor and maneuvered the two ships closer to the bay. At around ten o’clock at night, Barnet closed the gap between the ships. He readied his men and hailed Rackham’s ship with the British flag as a warning and a chance to surrender.

Across the water, Anne and Mary saw the flag and notified Rackham. He joined the women at the helm, swaying from drink, and took in the sight of Captain Barnet’s small fleet. Barnet stood at the helm with a hand in the air ready to strike the signal to load the guns.

“Jack Rackham, from Cuba!” he shouted across the water.

Rackham steadied himself and shouted that he would give no quarter, meaning that he would kill everyone. Anne and Mary urged Rackham to stand down, knowing that their ship and crew was no match for Captain Barnet. Rackham ignored their advice and ordered his crew to ready the guns. The pirates scrambled to prepare their weapons.

That was enough for Barnet. He gave the signal to fire his cannons. The shot tore into the broadside of Rackham’s vessel. In a drunken panic, Rackham ordered the men to go below deck.

“If there’s a man among ye, ye’ll come up and fight like the man ye are to be!” Mary shouted to the crew. They did not answer her cry and several of the pirates called for surrender before locking themselves below.

Anne and Mary, disgusted with Rackham and his craven retreat, armed and readied themselves, prepared to fight to the death as a pirate crew of two. Captain Barnet and his men boarded the ship and began to engage the women in brutal combat. The battle was lost before it began. Overwhelmed by their enemy’s numbers, Anne and Mary were subdued. The ship was lost. The next day Captain Barnet turned over Anne, Mary, Rackham and the rest of the Revenge’s crew to the charge of Major Richard James, a local militia officer, who threw the pirates into jail in Spanish Town.

November 1720

The crew languished in prison for the next several weeks until their trial commenced. Their cell was cold and damp, despite its tropical location of Jamaica in the West Indies. Jack Rackham and the male members of his crew were tried for their crimes on November 16, 1720 and easily convicted. Their execution was scheduled for two days later.

On the morning of the 18th, Anne Bonny and Mary Read were rudely awakened by the prison guards. They glanced at each other and steeled themselves with grim determination. Their own trial was not for another ten days, but for all they knew the hangman had come early.

The guard opened the cell and dragged Anne out, leaving Mary alone. The guard led her to another part of the jail she had not seen before. When they stopped, she looked upon the gaunt, desperate face of Rackham.

Rackham grasped the bars and told her tearfully that his day of execution had arrived. In a few hours’ time he would hang for his crimes of piracy in Jamaica’s port town and former pirate haven, Port Royal. He begged her for words of comfort to take to his grave. Anne just stared down at him without an expression on her face. Tears streamed down his face as he pleaded to her. To her, he was another man who had disappointed her, and broken the pirate code.

“I’m sorry to see you here,” she said. “But if you had fought like a man, you need not have been hanged like a dog.”

With that, she was escorted away and never saw her former husband and captain again.

She was led back to her cell and left to contemplate her own looming fate. She and Mary had much to think about. They were intelligent and resourceful women. The fate of captured pirates was not lost on them. Their fight was not over yet. With any luck, they might be able to spare their lives, at least for a little while, by doing what they had all along — outsmarting the men around them.

The Trial

With the rest of their crew hanged, Anne Bonny and Mary Read were tried together. They pled not guilty for their crimes despite several witnesses, including sea captains Thomas Spenlow and Thomas Dillon, and a former hostage named Dorothy Thomas, all of whom had been their prisoners at one point.

The most damning statements against the women came from Thomas and Dillon. Thomas gave a vivid description of their ferocious actions: “Each of them had a machete and pistol in their hands, and cursed and swore at the men that they would murder me and that they would kill me to prevent me coming against them.”

Dillon offered the final testimony. “Anne Bonny had a gun in her hand. [Anne & Mary] were both very profligate, cursing and swearing much, and very ready and willing to do anything on board.”

These two reports confirmed to the court the duo’s violent and evil behavior. There could be no reprieve at this point. After all the witnesses provided their testimony, the prosecutor turned to Anne and Mary and asked, “Do you have any defense to make, or any witnesses to be sworn on your behalf? Would you have any of the witnesses, who had already been sword [testified], cross examined? Do either of you have questions to be asked?”

Anne and Mary both replied, “We have no witnesses or questions.”

The prosecutor now granted the women a final word about their crimes. “What have you to say?” he asked them. “Whether are you guilty of the piracies, robberies, and felonies, any of them, in the said articled mention’d, which had then been read unto you? Or not guilty?”

“Not guilty,” replied Anne and Mary together.

On November 28, 1720, they were both found guilty of piracy. At the end of their trial the judge said to them, as recorded by the court:

You Mary Read and Ann[e] Bonny, alias Bonn, are to go from hence to the Place from whence you came, and from thence to the place of Execution; where you, shall be severally hang’d, by the Neck, ‘till[sic] you are severally Dead. And God of Infinite Mercy be merciful to both of your Souls.

The two women would not be taken easily, however. According to the trial transcription, “…both the Prisoners inform’d the Court, that they were both quick with Child, and prayed that Execution of the Sentence might be stayed.”

Dumbfounded by this turn of events, officials took the women from the court and submitted them to an examination. Sure enough, they were both pregnant, presumably by Jack Rackham. Not only were the women with child, they had fought with warlike ferocity while pregnant. This shocked and horrified the court more than their piracies.

Public executions were widely attended by local communities in England and the American colonies, especially those of pirates. But sentencing women to hang for their crimes was already controversial during the eighteenth century. Hanging two pregnant women would cause an uproar — even if the condemned women were pirates. The judge relented and offered them their stay of execution. This meant that after they each gave birth they would hang for their crimes. It was not a pardon and they were not free from the prospect of capital punishment, but they were at least given more time.

In the end, neither woman ever saw the noose, but a particularly cruel punishment was in store for the two lovers who had fallen so hard for each other and changed pirate history forever. Once the trial ended, they were led back to the jail and placed into separate cells far enough apart so they could neither see nor speak to each other again.

April 1721

Five months after her sentencing, Mary Read fell ill with a fever. After several days she died in prison. It is not known whether or not she had her child. Even her burial has never been confirmed. Some believe that she was buried in St. Catherine’s Parish in Jamaica, but her name never appeared on any official document.

Anne Bonny’s fate is more opaque. Her execution was never recorded and rumors have circulated for generations about what happened to her. She very well may have been executed, with records later lost. According to historian David Cordingly in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, other clues suggest that Anne’s father ransomed her out of prison and took her home to South Carolina. There she gave birth to Rackham’s child. In 1721, according to these scenarios, she married a man named Joseph Burleigh and had eight more children and died in 1782.

Female pirates were unique: not only did they upend the social system, they were marginalized figures who transcended their social positions, proving that women were just as brave, self-sufficient, and defiant as men, in the process inspiring generations. Their tale turned out to be extremely popular for the rest of the eighteenth century. Advertisements for the 1724 book A General History of the Pyrates listed the names of dozens of pirates profiled. Smack in the middle, the ad promised “the remarkable actions and adventures of the two Female Pyrates Mary Read and Anne Bonny,” with their names in a bold font that dwarfed all others.

No doubt the women themselves would have proudly appreciated their immortal places in the pantheon of pirate legends. When they faced the gallows, their lack of fear reflected their self-realization. “[Hanging] is no great hardship,” Mary mused. “For were it not for that, every cowardly fellow would turn pirate and so unfit the sea, that men of courage must starve.”

DR. REBECCA SIMON earned her PhD from King’s College London in 2017 with a specialization in the history of pirates and piracy.

For all rights inquiries for this and other Truly*Adventurous stories email here.