WHEN A NUCLEAR SPY SATELLITE PLUMMETS TO EARTH AT THE HEIGHT OF THE COLD WAR, AN ELITE BUT UNTESTED EMERGENCY RESPONSE TEAM IS CALLED INTO ACTION. THE UNKNOWN TRUE STORY OF AN INTERNATIONAL DISASTER IN THE MAKING.

ON A COBALT MORNING two weeks before Christmas in 1977, two men from a little-known nuclear emergency response team met in a secure room in Las Vegas.

“Do you mind if I close the door?”

Troy Wade stood at Brigadier General Mahlon E. Gates’s office door. Gates nodded.

The Brig. General had a warm demeanor belying his brilliant military career. As commander of a sprawling Nevada test site responsible for the vast majority of the nation’s nuclear tests to date, he oversaw hundreds of personnel in one of the country’s most secure and highly secretive facilities, which was tucked away in the desert a short distance from the gleaming casinos of the Las Vegas strip – casinos whose betting floors routinely trembled with the repercussions of the subterranean nuclear tests carried out under Gates’ efficient watch.

Among Gates’ many responsibilities, he considered one of his most important to be his creation and oversight of the Nuclear Emergency Search Team (NEST), a secretive fast response unit made up of the nation’s best and brightest civilian scientists and military personnel and equipped with state of the art detection and computing equipment. In a state of constant readiness, the unit could be called up and deployed at any time in response to nuclear threats at home or abroad, the tip of the spear for the most unthinkable calamities of the nuclear age.

“I’ve just had a phone call,” said Wade, Gates’ deputy.

Trim with a small black goatee and a usually calm demeanor. Wade now looked ruffled.

“I’ve been told that a satellite belonging to the USSR, powered by a nuclear reactor, is expected to impact Earth between April and June.”

The words hung in the air. A spy satellite – part of the USSR’s radar ocean reconnaissance array – was going to crash to earth carrying a nuclear reactor.

NEST had been created a few years earlier, in 1974, following a bumbling government response to a domestic nuclear threat that had turned out to be a hoax. The U.S. government realized it needed a more specialized approach to domestic nuclear incidents, a fast response team with the technology and know-how to give the nation a fighting chance. The problem with maintaining such a team in a state of readiness was that such incidents of this sort were exceedingly rare. Until then, NEST had primarily been deployed to lend a hand with industrial accidents, leaving the team untested when it came to significant threats to the public. A nuclear satellite careening to earth was the real deal, just the nightmare scenario that Gates had created NEST to deal with.

But there needed to be more to go on and no sense of where the satellite would come down. The only solace was the April-June timeframe, which meant Gates and Wade had a minimum of four months to stage their deployment.

Within days, however, that timetable crumbled.

QUENTIN BRISTOW loved a challenge. He was a man out of time, the sort of multidisciplinary savant who survived best beyond the confines of academia or corporate research. The Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) suited him just fine, even if he didn’t love bureaucracy. Now, after an internal reorganization – yet another in a series of shuffles and restructures – he found he had inherited a challenge suitable to his intellect.

The GSC needed a new instrument to detect gamma-ray radiation from the air, which would be an important tool for mining and geological survey use. The existing sensors were obsolete, and Bristow was tasked with creating a new device using cutting-edge technology, cramming it all into a small enough package that the device could be loaded onto an airplane and used during flight.

Bristow immediately turned his attention to the scintillation detectors on the old device, twelve cylindrical crystals packed into a sheet metal box that formed the heart of the gamma-ray detecting apparatus. Innovating a new configuration for these delicate crystals, Bristow wagered he could massively increase the sensitivity of his device while reducing the complexity of the onerous calibration steps, which had to be done nearly constantly to keep the detector “in tune.”

To power the computational output, Bristow and his team turned to NOVA minicomputers from the Data General Corporation. He had to devise an operating system for the computer that would be responsible for: “acquiring navigational, airspeed and altitude data, magnetometer data, keeping track of keyboard inputs and executing them in between the higher priority tasks, updating the display, doing the calculations necessary to process the gamma-ray data, and finally recording all the data once per second on magnetic tape.” The computer he used had just 32 kilobytes of memory available for all those tasks.

Bristow devoted weeks to developing an innovative interactive graphics display, a novelty that rendered computed information as a visual graph on a screen in real-time in addition to recording the data for later examination. He was worried the graphics interface was a waste of time, the sort of extracurricular brain teaser he was prone to be distracted by, but by the autumn of 1977, with the device finished, he was pleased with how functional the screen seemed to be.

The only thing that remained was testing. Aside from a single test flight, which went reasonably well, the Ottawa winter counseled holding off until the spring of the following year. There was no rush. While the GSC provided Bristow ample opportunity to stretch his creative mind, its work tended to be slow and methodical, not exactly life or death.

Bristow looked at his creation admiringly, and with that, he packed his untested device up for what he assumed would be a long winter hibernation.

COSMOS 954 was spinning wildly out of its orbit. The U.S. National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter, Zbigniew Brzezinski, summoned the Soviet Ambassador to the U.S. to the White House. Brzezinski, a Polish-American academic with a sharp wit and a long history in Washington, sat down with Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, whose previous career as an aerodynamic engineer would have given him a unique understanding of the unfolding catastrophe.

The Soviets had launched Cosmos 954 a few months prior from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in southern Kazakhstan. Though its official purpose was a secret, it was enough for a spy satellite. But a malfunction caused it to lose altitude and tumble out of orbit. The American military had been tracking the satellite, and now Brzeniski pleaded with his Russian counterpart for information that would help organize a response, insisting a crash posed a “serious hazard to the public” if it fell in a populated area. The core of the satellite contained more than 100 pounds of enriched uranium-235, about the same amount of uranium as the bomb dropped over Hiroshima. Brzeniski urged the Soviet Ambassador to help the White House prepare “appropriate measures to be taken to obviate such dangers” by providing technical details about the satellite.

Dobrynin said he would raise the message urgently in Moscow. Brzeniski, though, feared Cold War politics would forestall any meaningful cooperation. A 1971 agreement between the U.S. and the Soviet Union provided an immediate exchange of information regarding unidentified space machines, deemed essential since both sides had nuclear response protocols for any perceived attack involving foreign projectiles. Theoretically, the satellite now tumbling haphazardly to earth should have initiated such an exchange of information, but both sides tended toward denial in matters of spy technology.

Brzeniski held another meeting with Dobrynin on Jan. 17. Two additional phone calls followed but yielded no concrete details about the payload or the satellite’s design – information critical to understanding what they were against. Could the uranium on board reach critical mass and explode upon re-entry into the atmosphere or impact? It wasn’t a far-fetched notion. For all the brainpower and resources that went into the development of the first atomic bomb, its most essential element consisted of little more than a projectile that shot one lump of purified uranium into another. Modern thermonuclear bombs accomplished the same feat with extreme heat. A satellite burning up on reentry and plummeting to earth posed a genuine concern.

Dobrynin insisted the satellite reactor could not reach critical mass similarly. Still, with the Russians remaining tight-lipped about any technical details, there was no way for the American response to know for sure.

Meanwhile, analysts at the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD), roughly half a mile into the pink granite of Colorado’s Cheyenne Mountain, had been closely tracking the satellite’s demise. Circling the Earth roughly every 90 minutes in a tightening spiral, it was clear that the failsafe mechanism, designed to break the satellite into three pieces and launch them further into space in an emergency, had malfunctioned. Worse, the initial projection of four or more months now looked wildly generous.

As Brzezinski worked the diplomatic angles and NORAD continued tracking the erratic satellite, Gates and his NEST team jumped into action. The first order of business was dialing in the time and place of re-entry.

NEST members Milo Bell and Ira Morrison, an engineer and a mathematical analyst working out of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, were assigned the task. They were civilians with a Southern California aesthetic – t-shirts and wrinkled pants – though they were accustomed to the studied monasticism of their secretive professions.

The pair utilized a Control Data Corporation 7600, a hulking computer considered one of the most advanced in the world. Squirreling themselves away and inputting the few known variables plus best guesses supplied by colleagues in government and defense, they began to rough out a non-dimensional range curve that doesn’t follow any predictable trajectory. But the results of this theoretical curve kept shifting, the number of variables growing instead of shrinking with each critical hour. As the satellite neared the atmosphere, it began to skip, altering its speed and trajectory and triggering a new round of calculations. Bell and Morrison worked around the clock, anxiety mounting.

One thing was clear: The satellite would come down not in months but in days before the end of January. The question was where.

With time running out and little cooperation forthcoming from the Soviets, Brzeniski signed a directive alerting the Central Intelligence Agency, NASA, and other relevant governmental agencies. The Department of Energy sent a representative to a committee helmed by the National Security Council. The official line was that the committee had convened to address “a space-age difficulty ... there is no danger.” In reality, those involved in the government response were preparing for a calamity.

Back at Livermore, on the night of January 23 and having had almost no sleep for the previous four days, NEST members Bell and Morrison had finally recognized a recurring pattern in their massive computer’s output. The graph terrified them. With increasing frequency, and as Cosmos 954 was entering its final orbits, the probability that the crash would fall within North America was rising.

As news spread within the small community of analysts and military personnel in the know that the initial timetable was wildly mistaken and that an impact in North America looked probable, no one quite grasped what to do next. One of the NEST experts on standby, William Ayers, a health physicist who briefed U.S. Air Force personnel on radiation fallout hazards, braced for the worst. Were the satellite to careen through the atmosphere and fragment over a major metropolitan city, “My recommendation would be to evacuate the goddamn place,” he said.

At 2:00 A.M. on January 24, Milo Bell picked up the phone. NORAD reported that the satellite was entering its final orbit. Reentry would commence at 3:56 A.M. Pacific Time, and impact would occur at 4:17 A.M. based on all the available inputs. Bell and Morrison updated their calculations. The exact impact area was still uncertain, as was the consequence of reentry and a subsequent ground strike. Would the satellite explode? Would it vaporize, create a radioactive cloud, or plummet to earth in chunks?

The scientists finally determined that the likeliest point of impact would be somewhere in Canada’s Northwest Territories. This was good news in one respect: The area was remote and largely unpopulated.

Bell and Morrison referenced a map. There was just one town near the likely crash trajectory, a small mining outpost on the edge of the Great Slave Lake called Yellowknife, the unassuming capital of the Northwest Territories. With nothing left to do but wait, Bell checked the current temperature in Yellowknife: It was minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

JANUARY 24, 1978

The world beyond Jimmy Doctor’s backyard was still. Neighbors and their pets snoozed in the early morning hours. Little happened in the mining town of Yellowknife, nestled along the western shores of the Great Slave Lake in a foreboding landscape in Canada’s Northwest Territories known only as the Barrens.

The landscape added to the isolation and, for a certain kind of resident, to a welcome sense of peace. Caribou vastly outnumbered people, and with innumerable lakes and rivers, there is more water north of the sixtieth parallel than land.

It was a typically quiet morning. Then, the Doctor heard something out back.

He turned away from his radio and went toward the back door. Through a window, he saw a dog seated near his snowmobile. The dog was howling at the sky. When Doctor looked, he saw a careening curtain of orange molten light. The doctor ran outside. “I thought it was a plane on fire. I didn’t know what it was,” he later recalled. “It sounded like air coming out of a tire.”

At about the same time, Peter Pagonis was outside his home on 54th Street in Yellowknife, where he was hitching his truck to a series of water tanks. As he worked, something in the sky caught his eye. Three bright objects pierced the silence. He mistook the streaks of blush red and incandescent trails for a laser beam, like one he’d seen on one of his television programs. Pagonis hopped in his truck and navigated the familiar morning route toward the airport, where he delivered large drinking water tanks to a military aircraft hangar. When he arrived, he relayed what he saw to the corporal on duty.

Elsewhere in the Barrens, in Hay River, 125 miles south of Yellowknife, two Canadian Mounties suddenly brought their patrol car to a halt in the wintry outback. They stared as a fireball hurtled across the night sky. Corporal Phil Pitts saw a “bright white and incandescent” object that he believed was a meteorite.

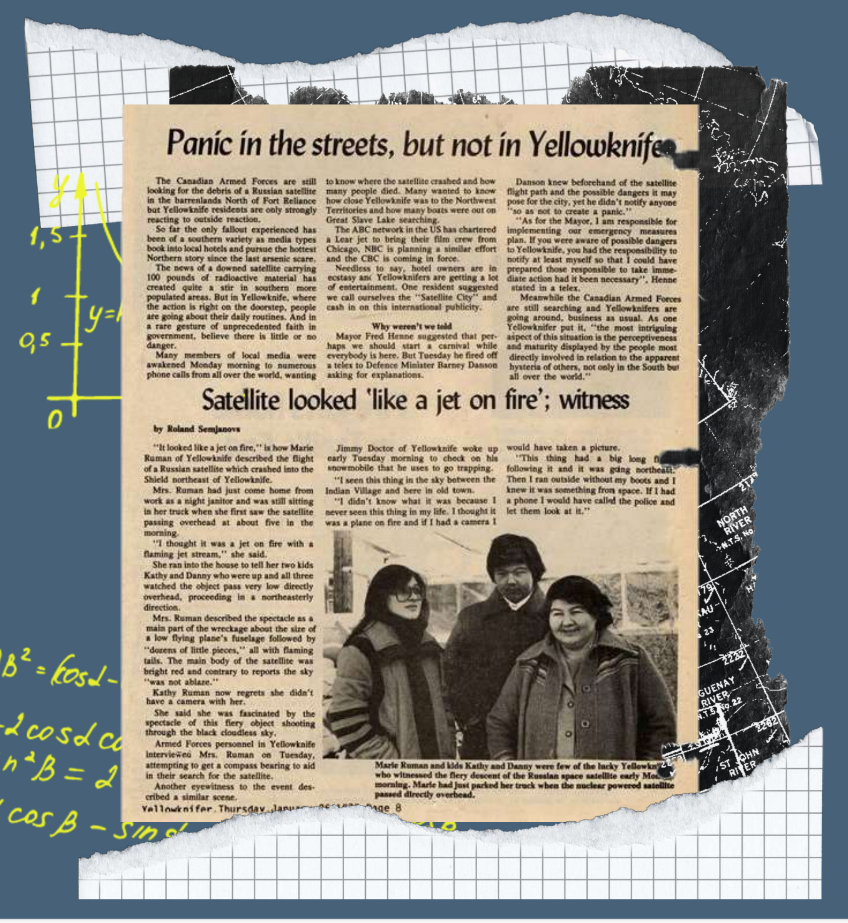

Having just arrived home from a night shift cleaning the offices of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Marie Ruman— middle-aged and a member of the Dogrib tribe—saw what she believed to be “a jet on fire with a flaming jet stream.” She couldn’t be sure where the streak was headed but believed perhaps it was northeast. She ran from her truck into her house to get her two children. The three bundled together outside their small frame house and peered upward to watch the flaming debris disappear along the horizon, spewing and hissing over a population unaware. Marie, a religious woman, believed she was witnessing the Second Coming. She crossed herself.

“JOE,” said General Gates, head of NEST, through his secure phone in Las Vegas. He was speaking to General Joseph Bratton, his superior in Washington. “I need five C141s.”

“What’s going onto the planes?” Gen. Bratton asked.

“Everything we have,” Gates replied. “Our total capability.”

“Is it that serious?”

“Yes,” came the terse reply. “I think it is.”

Reports of the mysterious object falling near Yellowknife prompted a series of calls between U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Canada’s Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. In a rapid-fire sequence, the U.S. offered, and the Canadians accepted on-the-ground assistance from the American military.

With three huge C141 jets spooling up on military bases around the country, NEST members created and crammed every piece of equipment in their arsenal to prepare for a journey to a remote place known locally as The Barrens. The equipment included two small helicopters jammed with electronic surveillance gear, unmarked bread vans that carried data processing banks, several dozen hand-held radiation and infrared counters, gamma and neutron detectors, a microwave ranging system, and aluminum containers stuffed with other gadgets. The list was extensive, the technology one of a kind and irreplaceable, and it crossed the minds of more than one NEST member that consolidating it into three planes set to fly into arctic conditions carried a catastrophic risk. But there was no choice. Within hours, the aircraft were taxiing down the runways. In addition to the equipment, they carried 113 American scientists, technicians, and secretaries, a mobile command and response unit representing some of America’s most valued human, military, and technological assets.

Beneath the planes, the landscape began its inexorable change. Cities gave way to towns and smaller settlements, and then civilization seemed to give way to a wild sub-arctic frontier. Tones of white and gray below suggested a barren, frigid landscape.

General Gates and his second in command Troy Wade would lead the American response, now codenamed Operation Morning Light. The planes descended toward the 14,000-foot Canadian Armed Forces base runway outside Edmonton, Canada, known as Namao. Previously a staging base for aircraft and supplies headed to Alaska and the Aleutians during WWII, Namao was the closest facility of any suitable size to the crash site.

Second-in-command Wade had been coordinating with the Commander of Namao, Colonel David Garland, who had been frantically preparing for the arrival of the large American contingent. Any notion that the recovery would be straightforwardly wilted as soon as the planes touched down. Garland, tasked with overseeing frequent rescue missions in the Canadian wilderness, knew how difficult it was in pleasant weather to search for a single human being lost in the rugged landscape, even if that person could proactively signal for help. It was winter, and the coldest months of the year lay ahead. They were likely searching for small fragments of metal. It was a tall order, a recovery operation that was wholly unprecedented.

The Namao base had been on high alert since word of the satellite’s impact reached Garland. He moved the Americans into the second floor of a massive hangar, but there was no time to settle in. Base personnel immediately began transferring the just-landed American equipment to a Canadian C130 Hercules, which would be piloted by the base’s search and rescue pilots, who would remain on 24-hour readiness. Aware that the Americans, many of them coming from the deserts of Nevada and California, would be out of their element, Garland had taken it upon himself to order arctic suits from army stores. The suits consisted of nylon outer boots with an inner fur-lined layer, woolen caps, special padded gloves, a quilted army parka, and thick trousers. It was enough to keep a man alive for a stretch in the -50 degree conditions, and it would be essential equipment for the American search team. A mission planning group under Garland would unify the different tasks of Canadian and American personnel, and Garland was responsible for integrating everything. The first search flight was scheduled to leave the base within two hours of the Americans’ arrival.

With his full capabilities deployed and on the ground, and with decision-makers in Washington turning their full attention to the unfolding disaster, NEST leader Gates felt a surge of anxiety. He knew only too well that the future of NEST hung in the balance.

Gates had lobbied hard and created the organization in the aftermath of major nuclear disasters that showed a complete lack of readiness on the part of the United States and its global allies. In 1965, a B52 bomber carrying four plutonium bombs crashed in Thule, Greenland. In 1970, another bomber carrying nuclear weapons crashed off the coast of Palomares, Spain. The global nuclear arsenal was proliferating, and accidents like these were bound to happen again and again. It was also impossible to ignore the possibility of individual actors getting their hands on nuclear weapons. In 1976, Princeton undergraduate John Aristotle Phillips designed a nuclear weapon as part of an undergraduate term paper. Subsequent analysis showed that the plans were remarkably accurate and a bomb made from them would likely function, driving home the clear and present danger of the nuclear age.

And yet, not everyone took the threat seriously, including some members of Congress whose support was critical to Gates’ efforts. Gates had made it his mission to create a standing task force with the equipment, scientific know-how, and response capability to deal with such catastrophes. But since NEST’s creation in TK DATE, the task force had mostly responded to minor industrial incidents that could quickly have been resolved without such a significant outlay of resources and personnel. Gates had faced skepticism from some lawmakers about the necessity of his group. Now, NEST had become the overseer of a veritable operation doomsday. It was everything Gates had feared and prepared for. And it could be his first and last chance to prove what his team could do.

THEY HAD HEARD the stories before: government men, white men, assuring them that nothing was the matter. Meanwhile, dogs were dying, and people were getting sick.

In a previous iteration, the threat had been arsenic, a byproduct of mining activity that poisoned the water and left Chipewyan and Inuit with unexplained illnesses. The Inuit had hired a lawyer to stop the government from granting permits to prospects. The game was being frightened away. But the white man’s appetite for what lay under the ground did not bow to that reason.

Florence Catholique, known as the settler chaperone at the Chipewyan settlement of Snowdrift, some 100 miles from Yellowknife, eyed a Brigadier General who now sat in the settlement’s recreation hall with suspicion. She had heard it all before.

Through a translator, the Brigadier General assured the gathered Chipewyan that no harm would befall them due to the satellite. In the same breath, he warned they might see activity in the area, men in yellow suits scouring the ground, helicopters and airplanes overhead. They were not to interfere. And whatever they did, they were not to touch any strange fragments they may have encountered on the ground.

There was no word in the Chipewyan language for radioactivity. The translator, groping for some kind of equivalent, settled on poison. Any fragments they might find could transmit poison.

Catholique stared at the Brigadier General in disbelief. Who, she demanded, would warn the trappers who spent months in the wilderness to feed their families and had no radio or newspaper access? And who would warn the animals?

The Brigadier General shifted uncomfortably. There is no danger, he repeated.

THE PRESS didn’t take long to catch wind of the fallen satellite.

Reporters from the United States, Japan, Australia, and every significant European capital descended on the Namao base, where they were herded into a first-floor briefing area.

It became clear to the press that the Americans, while officially guests of the Canadians and there to offer support, were taking the technical lead on the response. Try as they might to keep out of sight, the American visitors, dumbstruck by the cold and scurrying around the base and town in great droves, stuck out like sore thumbs. Reporters harassed them at the Explorer Hotel and in the operational rooms at hangar five.

Public relations for the visiting Americans fell to a flack named Dave Jackson. Accustomed to briefing the press from Las Vegas regarding planned nuclear tests, carefully parceling out information that had been vetted and cleared, the unfolding situation in Yellowknife was entirely different. Jackson, a former reporter, felt the familiar rush of a breaking story, but this time, he was tasked with controlling it.

While not permitted to expose sensitive details of the search effort, Jackson turned to a familiar trick to sate the press: He blindsided them with a rush of technical information. Jackson had considerable knowledge of response protocols and nuclear physics, and his briefings became a study in abstraction and misdirection. The press pool scribbled furiously, trying to keep up.

Even Jackson, who had run the press circuit for years, was overwhelmed by the onslaught.

Ironically, the only Western newspaper that mainly seemed uninterested in the satellite recovery was Yellowknife’s own Yellowknifer, run by a cantankerous old-timer named Sig Sigvaldason.

On the morning of the crash, Sigvaldason had hardly dressed when the first call reached him home. The ice-glazed windows grew lighter as more calls came in, first from a reporter at the American Broadcasting Corporation and then the British Broadcasting Corporation from London. Journalists sought to charter boats and planes to set out on their expeditions to find what they could of the downed satellite. By the time Sigvaldason left for his office at the newsroom, it was mid-morning, and he’d learned the entire story from “the southerners,” his term for the reporters now flocking up from the U.S.

An elongated wood-framed building painted bright yellow housed the newsroom. Outside, a billboard declared, “Yellowknifer. Your local Newspaper.” Sigvaldson wore a patriarchal white beard and a cotton shirt with continuously strained buttons. He wrote the next issue (“published at least once a week”) with great skepticism. “I think we have a different perspective and a greater maturity than the southerners,” he said. He buried the satellite crash inside the day’s edition, running as the lead article on the front page, below the newsprint banner and its mascot black raven, the prosaic headline “Land and millions offer to nations called ‘beads and trinkets.”

The whole world may have been ending in his backyard, but Sigvaldason had a job to do.

AN AMERICAN U2 screeched high overhead surveying the entire grid from Yellowknife to Baker Lake. Simultaneously, jets were sampling air above Canada and as far away as Michigan for traces of radiation.

Results came up negative, which caused a collective sigh of relief but also exacerbated the challenge ahead. The enriched uranium core had not disintegrated into the atmosphere, but that meant it was likely embedded somewhere in the snow and ice below, creating a veritable time bomb. If unsuspecting people or animals were nearby, they could be irradiated. If the radiation froze into the snowpack or, worse, got into the groundwater, the consequences could be devastating for an untold swath of the North American continent.

The American gamma-rays were designed to operate from the skids of a helicopter. However, their usual operation zone was Nevada’s warm, dry climate. The scintillator detectors on the devices had no insulation, and thermal shock from the extreme cold could cause them to crack.

The devices were moved instead to Canadian C130 turboprop aircraft. On January 25, the first foray of Canadian Hercules took off from Namao with American detection equipment onboard. The aim was to investigate the entire reentry area in one sweep.

However, the operation ran into an immediate snag. The rock outcroppings of Canada’s Northwest Territories are rich in naturally occurring uranium, resulting in frequent positive spikes. It soon became apparent that only after taking the magnetic tapes off the aircraft and subjecting them to rigorous analysis would it be possible to distinguish between natural and artificial sources, a clunky process that added time and strained the workforce.

Twelve aircraft flew in grid patterns over the likely crash site for two days but found nothing of note. Hundreds of reporters waiting on the ground, growing tired of Jackson’s technical reports, were desperate for some news to advance the story.

An air of apprehension and anxiety mounted in those first few days. Gates, sleep-deprived and monitoring the incoming results closely, worried about the consequences of not finding the satellite.

As in answer to the collective prayers of those gathered at Namao, the Americans discovered a spike in the graph – a positive hit. Though an air of secrecy predominated, there was no keeping a secret of this magnitude from the ravenous press. In Ottawa, attempting to stay ahead of the developing story and perhaps to reclaim some agency during what was perceived as an American-led response, the Minister for National Defence declared victory. “It’s either radioactive debris, or the greatest uranium mine in the world,” he said.

It was neither. Electrical interference had caused an anomalous blip. The satellite remained unaccounted for. The incident caused great embarrassment in the Canadian government and increased tensions on the ground between the international teams. The Calgary Herald carried the headline, “Faces are red in Ottawa over satellite confusion.” For the Canadians, a measure of national pride was on the line.

The satellite simply had to be found, and there could be no more screw-ups.

QUENTIN BRISTOW with the Geological Survey of Canada, got the call at about ten in the morning. For a scientist used to working in a staid, bureaucratic organization, the urgency on the other end of the line was eye-opening. A downed satellite, enriched uranium, the Americans needed help.

It was sheer coincidence that Bristow had just put the finishing touches on his new and improved gamma radiation detector, and the fact that it remained untested hung in the air as he rushed to make ready for a hasty departure.

The first step would be to transfer the device to a waiting aircraft that would take it and Bristow from Ottawa to Edmonton. The unit was massive, about nine feet long, and weighed hundreds of pounds. A heavy snowstorm had blown in, complicating the first logistical challenge: how to get the equipment from the hangar to the airplane. The detector was designed to fit onto a dolly that a small van could tow, but the cart had no springs and no protection from rain or moisture. Even a tiny drop on the sensitive circuits could render it useless.

Bristow and his colleagues found some plastic sheeting and began earnestly taping it. Hooking the dolly to the van, they peeked outside and sighed before moving the hundred-thousand-dollar equipment into a howling storm. It took half an hour to navigate the maze of runways, and when they arrived at the waiting plane, they discovered it loaded from the side of the fuselage, not from a rear cargo door as they were expecting. This meant the 1200-pound device would have to be twisted into the airplane awkwardly by military personnel accustomed to tossing far more durable cargo around. Bristow and his colleague watched in horror as the men manhandled the massive box, occasionally letting a strap slide off, which caused a corner of the device to thud against the cargo bay floor. At last, they managed the intricate maneuver, and the plane could take off, but Bristow wasn’t sure his device had survived this first test.

Arriving at Namao, the men from the Geological Survey were stunned at the circus before them. More than a hundred American personnel and many more reporters were thrumming about the place, a frenzy of nerves and anticipation. The false hit had embarrassed plenty of journalists and caused American personnel to backtrack, and everyone was on edge.

Bristow hardly had a moment to catch his breath. The new gamma detector was transferred to a waiting Hercules aircraft, where personnel again manhandled it. When it was in place, Bristow braced himself and turned the machine on. To his relief, it came to life, and a subsequent check of the scintillation detectors showed them to be in working order. He had packed the machine with significant foam insulation for the cold, and he realized with gratitude that it had doubled as shock absorption.

Where the Americans had a whole team capable of using their equipment, Bristow was the sole person with a detailed understanding of how to use the detector he’d built and programmed. He gamely said he was ready to go up immediately. Despite being sleep-deprived, the Hercules took off.

It took two hours for the plane to reach the probable crash site and then another eight hours to cover a portion of the grid area. When the Hercules finally returned to base, word of a super secret Canadian detection system had leaked. The press nearly attacked Bristow for information, and he parried with reporters while attempting to gather together a loose instruction manual so that colleagues at GSC could run the machine while he caught up on sleep.

Knowing he would be on deck again in a matter of hours, Bristow collapsed into bed, where he was asleep practically before his head hit the pillow.

THE TENSION at the Namao base was spilling over into Yellowknife, and soon, a rumor began to ping around town: The Soviets had spies on the ground.

An observer had noticed three foreigners who were not media and not dressed in the hulking snow costumes of the American and Canadian teams, opting instead for Siberian mukluks. The visitors weaved through the town with little interaction, occasionally scribbling notes. The suspicion was that the Russians had landed and were there to recover what they could or to at least monitor the activity of American and Canadian nuclear response efforts. A report was filed and reached all the way up to Danson, the Canadian Defense Minister, who was said to have ruled it plausible, citing the clumsy efforts of the Soviet Union to penetrate Canadian security services.

If spies were on the ground, it was clear evidence that there was more to the satellite than the Soviets had willingly shared. Were the spies hoping to recover technology? Or had the spy satellite been carrying sensitive information? The revelation brought a new note of anxiety to the already fraught unfolding situation.

Adding to the air of intrigue, one member of the NEST team, flying in from California and presuming his expertise to be of particular use to the operation, informed his Canadian counterparts before arrival that he wished to operate incognito. He planned to arrive at Fort Reliance, 500 miles north of Edmonton, with a brown attaché case. The briefcase contained a state-of-the-art radiation detection system that was more commonly utilized in urban settings, the small size allowing for discreet readings that wouldn’t alarm bystanders.

The idea, the scientist said, was that he would walk through Fort Reliance monitoring radiation without drawing attention to himself. Perhaps out of disbelief, or maybe from simple childish amusement, no one bothered to tell the scientist that there were no streets in Fort Reliance, just shacks built atop a mushy bog. Each shack was guarded by snarling, half-wild dogs, and the temperature was dozens of degrees below zero.

The image of a self-important scientist frumping around town inconspicuously in his suit and loafers must have made the Canadians laugh. Men with attached cases similarly traipsed through Yellowknife, a farce straight from the pages of a lousy spycraft novel.

Contributing to the otherworldliness of the events was a strange encounter at the very top of the Canadian Department of Defense. An official in Canada’s Foreign Liaison branch, helping coordinate the recovery effort, received a visit from Earl G. Curley, escorted by an official from the Department of Defense. Curley was 31 and nondescript with dark hair and a conservative suit, making it all the more surprising when he stated matter-of-factly that he was a psychic.

A year before the satellite had crashed to earth, Curley had predicted in Inner Life Magazine that a soviet satellite would come hurtling to earth. A day before Cosmos’ reentry, Curley had informed a U.S. Naval attaché in Ottawa that the satellite would strike the following day.

On the weight of his accurate predictions, Curley was ushered into the Foreign Liaison branch, where he now spent an hour describing his vision in detail. Curley claimed to have seen the entire reentry over the Yellowknife district. He said the satellite had broken into three main pieces and several smaller ones. The reactor was wholly or partially intact, he assured. He could give a precise set of coordinates.

The official told Curley to compile a report. The next day, the psychic returned with ten typed pages, including the coordinates. The official assured Curley it would reach the appropriate authorities.

The report did make its way to Namao, but it was promptly dismissed out of hand – likely amid a welcome flurry of laughter. The scientists conducting the recovery were practical and had no time for psychic visions. The coordinates, however, would later prove prescient.

A more immediately credible observation came the same day from a civilian source. That morning, a Swedish man named Costa Kruger left on a Scandinavian Airlines flight from Stockholm en route to Seattle and then San Francisco. Though he was flying as a passenger on the flight, Kruger had spent 30 years as a navigator for the airline flying the Polar route to the U.S.

On the flight, Kruger noticed that the flight plan took the plane along the familiar flight plan Charlie to the northeastern coast of Canada, where a series of terrestrial beacons helped guide the aircraft. Kruger knew the route and the terrain; like everyone else, he had heard about the downed satellite in the region. A little after 2:00 p.m. local time, on an obvious day, the sun blinked on the frozen lake below. The smooth, wind-blown snow on the lake surface was an unchanging white, and Kruger mused how difficult it would be to make the slightest progress on the ground in such conditions.

Suddenly, something caught his eye. It was an unnatural opening in the ice. Tiny from the sky, it must have been 500 to 1000 feet in diameter on the ground. Over the hole was an extensive vapor trail that drifted west-southwest. There was no doubt that this was a crash site of some kind.

After pressing his face to the window for a few minutes, Kruger hurried to the flight deck. The crew knew him, and although none had seen the crash site out the window, they readily gave him the latitude and longitude they had just flown over. Kruger thanked them but puzzled over what to do next. He decided to write a letter, which he could give to the ground crew when he landed to change planes. In the letter, Kruger identified himself and his credentials and described the crash site and the coordinates. In Seattle, he handed the letter with instructions to the ground crew.

Airline administrators passed the letter to the Police Department of the Port of Seattle, which forwarded it to Security Police at McCord Air Force base. Finally, the letter was sent urgently to the Department of Energy and then telexed to Namao. There, it was promptly lost amid the frenzy of the ongoing search. The hole in the ice was south of the suspected landing site, and perhaps on that basis alone, no one bothered to follow up on it.

THE GAMMA DETECTOR expert, Quentin Bristow, awoke from deep slumber and rushed to join the next search flight aboard the Hercules. The plane was kept in continual operation, 24-hour shifts with scientists and crews shuffling on and off. Bristow boarded the aircraft after the previous shift had been whisked off and, as a result, had had no interaction with his Canadian colleagues before taking off. The cargo door shut, more sealing in the frigid cold than keeping it out. The plane rumbled down the runway and lumbered into the air.

Bristow was groggy and unprepared for the chaos awaiting him twelve hours later when the Hercules touched down at Namao again after an uneventful search. It seemed that the previous flight had found a large ping, a positive spike in the gamma spectrum, but hadn’t been able to confirm it until they were on the ground – until after Bristow had lifted off. Word of this spike, more definitive than the electrical interference anomaly, tore through the scientific teams at Namao, and it wasn’t long before the press caught wind of it. At long last, it seemed like proof positive of radioactive debris.

The only problem was that no one on the ground at Namao, neither the American experts nor their Canadian counterparts, could verify the exact nature of the spike or its precise location because only one man understood the peculiarities of how the data was formatted: Quentin Bristow.

When the Hercules door opened and Bristow stepped out, he was mobbed by flashbulbs, a horde of clamoring reporters, and the anxious faces of his colleagues. Bristow ducked the press and was escorted to one of the waiting information processing vans that the Americans had flown up from Nevada. Going over the magnetic tapes, Bristow was struck by a nagging thought: He had yet to do any work to verify that the data the sensors collected was correctly recorded on the tapes. This was, after all, essentially the machine’s trial run, and the possibility of gremlins in the recording program suddenly dawned on him.

Holding his breath, Bristow carefully analyzed the tapes. To his relief, all appeared in order. Sure enough, the spike revealed something telling: the presence of Lanthanum-159, a product of nuclear fission. They had found evidence of COSMOS-954 at last.

Rather than relief, however, this discovery led to a new panic. The satellite had indeed touched down, and now there was proof positive that a radioactive debris field existed, one that posed a tremendous risk to human life and the environment if not cleaned up.

Bristow later described the press response to this new information as changing the scene from a circus to the trading floor of a stock exchange. Information and sensitive assets were leaked, and Bristow had the surreal experience of seeing his machine and graphics display on CBC-TV that evening.

Canadian media celebrated the “Canadian system” built by one of Canada’s finest that had finally located the downed satellite. It was a point of national pride during an embarrassing moment of international cooperation that seemed to many to be more like an American invasion. Many of the media reports focused on how well-resourced the American teams were before exclaiming that the moxie of the Canadian scientists had broken through in the end.

Not that the day was saved. The finding only made the need for a recovery more urgent, and that was problematic. The radioactive spikes had been detected somewhere on the frozen expanse of the Great Slave Lake in a region virtually inaccessible in the winter. Locating the exact location would be troublesome, and there was yet to be a clear sense of how the team would contain and remove the radioactive material it found.

THE DOGSLED made a familiar sound on the hardpack, the clean slicing indicating motion and efficiency over snow.

It was only 3 pm, but the winter sun was already low in the sky. Mike Mobley and John Mordhurst were crossing the frozen Thelon River with their six-dog sled team. They were on a grand adventure and having the time of their lives.

Mobley and Mordhurst were Americans (Arizona and Illinois, respectively). Still, they had come north on a self-styled expedition to trace the route of a well-known explorer named John Hornby, who died in the region in 1927. Along with four others who were back at base camp, they were doing amateur fish and wildlife studies and passing meteorological information along to Canadian government agencies, a pastime the government had long encouraged in its remote northern regions.

As Mobley and Mordhurst took a corner, something unnatural caught their eye. In that vast snowy wilderness, the last thing they expected to see were pieces of metal. And yet there they were, twisted fragments inside a crater about eight feet across.

The metal included gnarled metal tubes and a bent canister. It was charred, the impact recent, though a few days’ frost had settled over the wreckage. Mordhurst reached out and touched the metal briefly with a gloved hand. He withdrew it quickly, noticing an irregular pattern of smooth black ice around the object. When the pair returned to base camp, they reported the find to their four colleagues. Equipped with radios, the group had heard about the downed satellite. The news had previously seemed remote, a problem facing the outside world, though now they wondered if ... maybe?

It took a few hours to contact Yellowknife via a relayed radio connection. It didn’t take long for them to receive a reply: They should not approach closer than 1000 feet of the object. Mordhurst, who had touched it, thought the caution was a joke and continued to think so when first light brought the sight of a Canadian Twin Otter aircraft, which touched down via skis right next to their camp.

“Unclean, we’re unclean,” Mordhurst jokingly shouted. The military personnel were not smiling. Before they knew what was happening, Mordhurst and Mobley were whisked aboard the airplane. Armed military men stayed behind to secure the scene. If Mordhurst and Mobley had been in contact with a highly radioactive material, they were looking at serious health problems and likely a drastically shortened lifespan. Though radiation is not infectious the way a disease is, there are cases where it stays present in body sweat for a short time and can cause collateral contamination that way, potentially imperiling the whole group.

The discovery caused practically the whole base at Namao to mobilize. A NEST geophysicist named Paul Mudra left immediately for the site on the Thelon River. It was a bright, sunlit day, although the temperature was dozens of degrees below zero. The cold air gave an extra sharpness to the ice-coated features of the four-foot-long contraption lying at the crater’s center. Mudra believed the debris to be part of the satellite’s propulsion system, and he could tell at once that it was not the core, which was the critical piece everyone hoped to find soon. On contact, Mudra’s detector showed 15 Roentgens of radiation, a hazardous level but one that would dissipate quickly in the air.

What confounded Mudra more than anything was the location of the object. All evidence indicated that the satellite should have reached farther northeast than this crash site. The positive pings they had found so far indicated this incontrovertibly, yet here was a big hunk of the satellite exactly where no one thought it would be.

Mudra returned to the Chinook. Its blades were still spinning, the engine staying warm. It was late, and the pilot was anxious to start the long flight back. As he looked below at the rough beauty of the Barrens, a horrible idea struck him. What if the core had disintegrated into a million tiny pieces?

Mudra wasn’t the only one to have considered this possibility. Robert Grasty of the Canadian Geological Survey kept a private record of the data collected on the search missions over the Great Slave Lake. A pattern began to emerge from the snippets and isolated hits as if someone had sprinkled a great pepper shaker full of radiation over the area. This was perhaps the worst of all possible outcomes short of a nuclear detonation. Yet the evidence increasingly pointed to a virtual hailstorm of radioactive fragments over a massive footprint.

Back at Namao, the press, starving for a good human interest story had caught wind of Mobley and Mordhurst, the amateur adventurers, and clamored for an exclusive story. After a frightening battery of tests and debriefings, Mordhurst was relieved to learn that he probably hadn’t been exposed to a harmful level of radiation. The military turned them loose, and for the next several days, the pair lived like kings in the fanciest hotel in Edmonton while entertaining offers from international media to tell their story.

IT WAS A LOT of territory to cover, eighteen thousand square miles. It was becoming clear that there were potentially thousands of tiny metal fragments in that vastness. It was the proverbial needle in a snowbank.

The Hercules, flying down the vast footprint, carried Bristow’s sophisticated sensor. This was the front line of the search effort. A special Hit Evaluation Panel carefully weighed the daily results of the search and decided the best way to proceed. If a spike on the screen were deemed, after analysis, as a likely positive hit, its location would be transmitted to helicopter teams who would try to locate the site and land with handheld detectors.

It was a laborious and clumsy process. Identifying the precise location of a piece of debris was also remarkably difficult. The object was embedded in snow, sending up a thin pencil of radiation that the ground team could easily miss. Technological improvements helped, such as implementing a one-of-a-kind microwave ranging system, but the work was tedious with no end in sight. One of the most effective recovery methods was one of the lowest-tech. When the Hercules found a potential positive hit, the crew would throw a streamer out of the aircraft onto the ground, a marker for the ground teams that would have to go back and search through the thick snow drifts.

Gates and the rest of the NEST team were simultaneously mired in the tedium of the recovery and also anxious, aware of the steady march of time. The coldest months were ahead, hampering the work, but the looming spring breakup presented a potential nightmare. If the radioactive debris found its way into the water supply, the health risks could be enormous.

Once located, the debris was shoveled into black plastic bags and placed in specially lined steel drums. These were stored in one of Namao’s underground ammunition bunkers until they could be shipped for analysis to the Whiteshell Atomic Energy laboratories in Manitoba. Lacking available military transports, the drums were first loaded onto commercial flights, where unknowing civilian passengers sat just feet from the encased radioactive material. This practice was stopped cold when Defense Minister Danson heard about it and exploded. After the public missteps of his office, he could only imagine the PR fallout if the press caught wind.

Under the strain, personalities began to chafe. Conflicting opinions and ideas about how to handle the recovery put members of the American and Canadian teams at odds. And while hundreds of pieces of debris were being recovered, there was still no sign of the reactor core, which was the critical piece of the puzzle.

To ease the logistical difficulties of the search, it was becoming evident that a forward supply camp would be necessary. Built on a christened Cosmos Lake, so-called Camp Garland sprang to life overnight on the four-foot thick ice shelf, which was wide enough to carry the 78,000-pound Hercules. Thermally insulated and heated tents popped up on the lake surface, prepared via a gigantic bulldozer that had to be parachuted outside a Hercules. The temporary base came together quickly, but it was lost on no one that its existence portended a tedious search ahead.

It was also lost on nobody that the satellite weighed some five tons. By the end of March, less than a hundred pounds of debris had been recovered. The governments of the U.S. and Canada continued to reassure the public that no threat existed. And yet, the men who had invented the Polaris, Poseidon, and the neutron bomb, the top nuclear physicists in the world, continued to occupy Namao and Yellowknife.

A RED SNOWMOBILE roared over the snow at the two approaching figures. The man on the gleaming machine, unnatural in the white wilderness, brought it to a skidding stop and jumped off before marching to intercept the approaching duo.

They were Chipewyan and had come to ask what was happening. Florence Catholique, the chaperone of the native settlement of Snowdrift, had been right in her skepticism. Now, her people’s land was beset by flyovers from helicopters that pounded the air and scared animals by an army of men with probes. Strange occurrences had been happening in the settlement. A wolf, the most evasive of forest hunters, had wandered into the village, evidently disoriented and sick. Dogs had died. Things were not okay.

The man on the red snowmobile gestured for the approaching Chipewyan men to go back. In a few days, the Brigadier General, acting as an envoy to the area’s native communities, would have to return to the recreation hall to reassure Catholique and others and repeat his warnings: Everything is fine, but please stay away from the recovery effort.

This hypocritical message was now becoming farcical, doubly so because a native had just made perhaps the most significant find to date, a chance discovery that could hold the secret to the pot of gold the scientists had been anxiously searching for.

At 1600 hours on March 10, a native seal hunter had suddenly braked his dog team of huskies, nearly turning over his sled in the process. The maw of a giant crater lay before him on the otherwise unbroken frozen expanse. The ice was five feet thick, but whatever had made the crater had plunged straight through to the water below, a skin of which had refrozen. Huge bricks of thick ice had been hurled hundreds of feet from the crater’s center, the result of some unthinkable force. The native man had never seen anything like it.

For anyone who had bothered to look at the report of Costa Kruger, the Scandinavian Air navigator who had reported a crater impact sighted from a commercial plane high above, this new finding must have triggered a connection. The crater site was far from the center of the NEST search footprint, and the nearest airfield was 250 miles east. At Namao, a Twin Huey helicopter was promptly disassembled and placed onboard a Hercules. NEST scientists were rushed aboard the transport. It was all hands.

Three days after the discovery, the Twin Huey’s blades thumped overhead. Scientists scuttled out of the belly of the helicopter, cautiously approaching the anomalous crate, detectors stretched defensively in front of them. The site of the crater on the ice was a shock, an unnatural contrast to the endless expanse of ice and snow-whipped frost all around.

Word of the crater had spread quickly through the area’s native communities. No one had heard of anything like it, and nothing in the elders’ stories or the shaman’s visions to the unnatural and hideous deformation. The people who knew this land best knew this was something new, something related to the frenzied activity of the white men, whose assurances were now so familiar.

The NEST men approached the rim of the crater and looked in. Within minutes, their military escort had set up a perimeter while the scientists deployed detector probes and set up an underwater camera. Everyone knew the ecological and human consequences could be incalculable. Contaminated water could enter the drinking supply, contaminated fish would be consumed right up the food chain. In this remote and unspoiled hinterland, potentially the last bastion of unfettered nature on earth, man’s quest for advancement, the ongoing race for technological superiority at any cost, seemed to be playing out.

And what of the human fallout, the panic, the lawsuits, the trampling of native lands, and the threat to future generations? Peering into the rim of the crater, the men of NEST, workmanlike in their approach, must have understood the consequences of what might lie beneath the ice. Indeed, the military hierarchy of the two nations, the Canadian Defense Minister who so feared a PR bonanza, and Gates, whose fragile creation, NEST, had a mandate to keep people safe and to effectively clean up any messes caused by nuclear accidents, understood the stakes. That crater, these men understood, could open a can of worms the likes of which the world had not yet seen.

The official story, released to the press, members of which were kept conveniently back at Namao hundreds of miles away, is that the crater was caused by a natural phenomenon known as an “ice boil.”

POSTSCRIPT

The saga of the downed satellite and the subsequent Operation Morning Light remains a largely forgotten Cold War incident. This is partly due to the lack of a definitive end to the cleanup effort.

Following the frenzied first weeks of the recovery, the operation dragged on for tedious months, culminating finally toward the end of 1978. In all, twelve large sections of the satellite were found, most of them radioactive. Some fragments were radioactive enough to kill a person with any kind of prolonged contact.

The Canadian government billed the USSR the equivalent of $4.5 million for cleanup and ongoing remediation efforts. Ultimately, the USSR paid some $2.25 million and quietly considered the matter settled.

Brigadier General Mahlon E. Gates’ work to build a tactical nuclear response and cleanup team turned out to be an enduring legacy. Following its work in Operation Morning Light, NEST found growing support among Congress and continues to be an integral component of the nation’s first-response capabilities. NEST helped during the response to the Fukushima disaster in 2011 and currently has more than 600 experts on standby and ready to deploy during a nuclear emergency.

Quentin Bristow, who designed the gamma detector that led to critical debris findings, had a long and fruitful career at the Geological Survey of Canada and became widely regarded in geophysicist circles. Owing in large part to his work during Operation Morning Light, he participated in several IAEA missions throughout his career. He died in 2014.

In the late 1970s, when Kosmos 954 came crashing down, there were hundreds of manmade satellites orbiting the earth. Today, there are close to 8,000. Some 30 or so are nuclear-powered.

To date, less than 10 percent of Cosmos’ radioactive material has been recovered. The radiation could still pose a potential human and environmental risk, particularly as long-frozen permafrost begins to melt due to global warming.

KENNETH R. ROSEN is an American writer, journalist and war correspondent based in Central Europe. He is the recipient of the Bayeux Calvados-Normandy Award for war correspondents and has been twice a finalist for the Livingston Awards.

For all rights inquiries, email team@trulyadventure.us.