He hacked into computer systems looking for secret government files on UFOs and almost started World War III. A real-life WarGames told for the first time through never-before-seen files, records and interviews.

Intruder alert. Intruder alert.

The recorded voice rang out again and again, a signal of possible global disaster.

It was the spring of 1994 at Rome Labs, the 1,000-person United States Air Force “superlab” in central New York State that operated as a command and control facility for military computing systems and the secrets contained within them.

At the sound of the alarm, exhausted operatives rushed to keyboards, pushing aside crumpled soda cans, ketchup-smeared burger wrappers, sleeping bags stuffed under tables, and guns. The investigators had converged here from two different departments, the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) and the Air Force Information Warfare Center (AFIWC), with competing protocols but the same goal: stop the hacking that was pillaging their systems. When AFIWC agents attempted to launch a “hack back” against their adversary, an AFOSI agent stopped them.

“That’s the same thing the bad guys are doing!”

“We’ve already been authorized to do it,” came the reply.

“Only the Department of Justice can authorize an attack.”

“This is an information warfare attack on the United States,” the AFIWC agent insisted. “So we can do this.”

An AFOSI team member opened his coat to show his gun. “If you do, I’m going to put handcuffs on you.”

The showdown captured a moment in time in one of the most significant cyberattacks in history, a multinational threat that raised tensions to a fever pitch and fundamentally changed how the world perceived hackers— launching a two-year global manhunt and transforming information warfare at the turn of a new century. Through interviews with sources speaking on the record for the first time, as well as never-released government, police, and court documents, Truly*Adventurous can reveal the complete story behind it.

In the windowless room in Oneida County, New York, the investigators stared each other down. For every moment of the impasse, the activity in cyberspace grew more dangerous. At one point, the mastermind hacker apparently seized control of FLEX–the Force Level Execution system–meaning their foe could set missiles to point to any country in the world that could wipe out millions, and the very act of which in itself could start World War III.

All because of a teenager looking for meaning (and aliens).

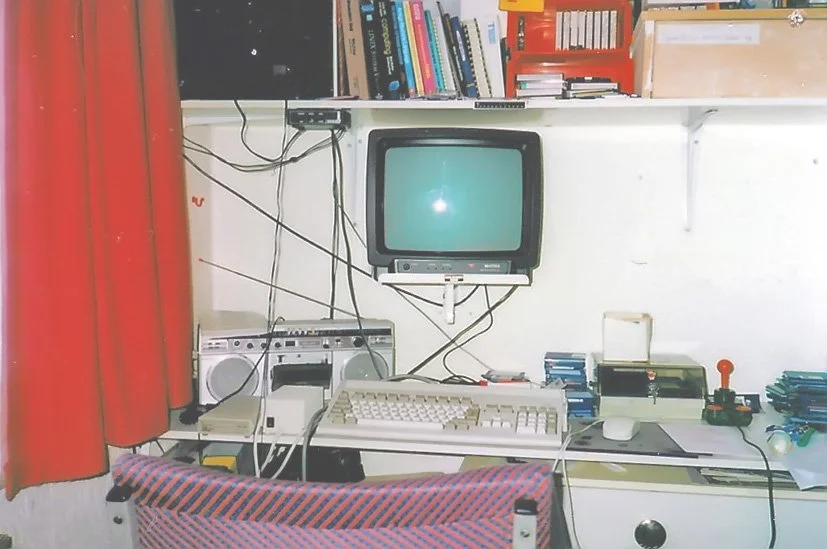

Weeks earlier, Mathew Bevan, 19, sat on a blue-and-red striped chair in his bedroom in Cardiff, Wales. Lean, with long dark hair tied back into a ponytail, he was dressed in a T-shirt and Bermuda shorts. Red curtains kept the eight by ten-foot room dark, which suited Mathew, who liked working at the computer late into the night, a silver boombox and a pile of cassette tapes beside his keyboard. Programming books lined the shelf above his desk, near the iconic “I Want to Believe” UFO poster from The X-Files. With his Commodore Amiga 1200 projecting to a monitor on the wall while connecting to the internet through the telephone line, his setup cost only £400 for what a British official soon claimed was “causing more harm than the KGB.”

Growing up, Mathew, like many kids, had trouble fitting in and struggled with unforgiving social environments that targeted insecurities.

“I was bullied almost every day of my school life,” he recalled. He was physically beaten during his early years of school, and as he got older, the abuse became verbal but no less hurtful.

He found an escape in the form of computing. On his 12th birthday, his parents got him a Sinclair ZX81 home computer and subscriptions to a few computer magazines. The inexpensive Sinclair hooked many of Mathew’s generation. He turned out to be naturally gifted at computing, and his father, Glyn, a police officer in the fraud squad of the South Wales Police, and his mother, Elaine, supported his interest, however hard it was for them to relate to it. At 15, he added a 2400 baud modem. For a month, he had called into every bulletin board he could find– electronic meeting places where users could share information and make announcements, a sort of early combination of soon-to-launch Craigslist and far-into-the-future social media. But soon afterward, his parents gave him “a real slating,” or reprimand, for the astronomical phone bill.

His genesis as a hacker came out of practical reasons: he did not want to give up his newfound hobby but also knew he could never rack up another egregious phone bill. He studied hacker bulletin boards and learned how to make free phone calls. He could now live much of his online life without leaving a trace.

Those computer adventures came long before the days of broadband, the type of fast, “always on” internet access that most computer users now take for granted. Mathew first mastered the basic hacking skill of dialing up online for free. Then, “like every aspiring hacker,” he began to hide his trail, “diverting” his calls “through several countries before reaching my destination,” a method called blue boxing.

“The hacking world,” Mathew said, “was pure escapism.” He could now endure the school day because, once he came home, he could “log on to another world. Somewhere I could get respect, somewhere that I had friends.” He found community and social life online and sometimes spent nearly 30 hours on his computer.

He especially thrived on international bulletin boards. “I began to make friends,” he once recalled. In what he called “the computer realm,” Mathew was “strong and fearless, even if I felt scared and powerless in real life.” He even gained the confidence to begin forming a genuine connection online on a late summer day with a woman in Texas named Lisa. After watching his police officer father always afforded almost automatic respect from the community, Mathew enjoyed earning respect for his rapidly developing computer skills. Online, Mathew would share his knowledge about phone phreaking, or attacking telecommunications systems to generate free calls, in exchange for hacking tips. Though anonymous, he no longer felt invisible.

“Hacking,” he once said, “feeds my addiction to information, love to learn, explore and tinker.” His first hack was at 15 years old in the form of the computer system of one of the world’s symbolic fonts of knowledge, Harvard University. He was naturally curious, and since he had found community with other hackers, he subscribed to the subculture’s primary ethic: “It’s the challenge of getting in that drives them, not the joy of mucking things up.” Mathew, metaphorically, wanted to get into the building—to look around, take it all in, and not smash windows or graffiti the walls.

He went on to study computing at the University of Wales Institute, Cardiff, but did not receive his Higher National Diploma. The program’s director, Mike Newth, had said Mathew was a smart student, “keen on the intricacies of computer systems,” but not interested in studies “which he didn’t immediately see relevant to the technical side of computing.”

Mathew Bevan had been generating his education.

Simon was an Australian hacker who went by Ripmax and ran a bulletin board called Destiny Stone. Simon was a prolific phone phreaker and particularly interested in alleged cover-ups. In January 1992, Ripmax was arrested by Australian authorities for phreaking. Investigators surrounded him at his office, while others were back at his house turning his bedroom “upside down” and confiscating his equipment. Interrogated for hours, Simon refused to give up the names of other hackers.

Mathew had been drawn to Destiny Stone because Ripmax shared one of his chief interests: UFOs. The X-Files poster on Mathew’s wall made the point: he wanted to believe. But he wanted more than that. He wanted evidence. He was fascinated by the alleged Roswell, New Mexico crash of 1947, convinced that the United States government had UFO information that they kept out of reach. Mathew downloaded and pored over as many as 500 texts that Ripmax collected.

Though Ripmax was put out of business by the police, Mathew remained committed to finding more. He followed his interest to an influential hacker e-zine, or electronic magazine, PHRACK, published since 1985. Sensitive documents published in the 1989 issue of the magazine led to a Secret Service raid and the arrest of one of the founding editors. It was another issue of the magazine that would change the course of Mathew’s life.

Dateline NBC, 1992.

The contents of the fateful issue in question could be traced back to a 1992 Dateline NBC episode that included a segment on computer hacking. An American hacker with the pseudonym Quentin was interviewed and several shots of his computer were included. In one, the text on the screen read “Wright Patterson AFB. Cataloged UFO parts list” as the segment’s narrator described how Quentin had “browsed through secret government files on UFOs.” (Not shown on screen, the entire sentence read: “Cataloged UFO parts list. Autopsies on record. Bodies located in underground facility of Foreign Technology Building.”) Another file image on screen referenced the life of Paul Bennewitz, a Coast Guard veteran turned businessman and UFO researcher, who reported lights over Kirtland Air Force base in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Bennewitz was subsequently alleged to have been the subject of a government disinformation campaign.

The segment was the talk of HoHoCon ‘92, an annual hacking conference in Houston that glibly invited “Hackers, Journalists, Security Personnel, Federal Agents, Lawyers, Authors and Other Interested Parties.” Online announcements for the conference cited “a large number of letters” asking about Quentin’s identity.

At the conference, Chris Goggans (known online as Erik Bloodaxe), who also appeared on the Dateline segment, was asked about the mysterious file on Quentin’s screen. Goggans was hacking royalty and an original member of the Legion of Doom, an infamous and influential hacking group from the 1980s, and an editor of the PHRACK e-zine. Goggans revealed that the file was discovered through a collective hack of military and government computers, known as “Project ALF-1” and “Project Green Cheese.” The hackers, whom Goggans refused to identify, aimed to uncover and distribute classified UFO documents and secrets.

Issue 42 of PHRACK, released in early 1992, connected Quentin’s research to rumors about “a group of hackers who were involved in a project to uncover information regarding the existence of UFOs.” The hackers discovered documents that described unusual propulsion systems, among other revelations and entranced Mathew.

Spurred by the claims made by Goggans and PHRACK, Mathew came upon another provocative rumor. One hacker, according to this tale, had accessed the internal network of TRW Space Research, a company that conducted military and space technology research (including the development of the first intercontinental ballistic missile). The hacker “has not been heard from since uncovering data regarding a saucer being housed at one of their Southern California installations.”

Mathew later claimed that 40 or more hackers involved in these projects disappeared, an apparent exaggeration of Goggans’s description or an amalgam of related bulletin board rumors. Regardless of the scale, Mathew was convinced that hackers had successfully penetrated the sensitive networks at government and military installations, and they had begun to collect and release classified material about aliens and UFOs, apparently at great risk to themselves.

Mathew focused on work by the Project ALF-1 group. In PHRACK, Goggans published the whole file that “Quentin” had been browsing during the Dateline episode. The document listed the names of individuals and military bases that the hacking group had targeted during their mission to unearth classified documents. Mathew noticed some overlap between the bases listed and the previous UFO documents that he had received from Ripmax: NASA’s Ames Research Center at Moffett Field Naval Base, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Holloman Air Force Base, Pentagon’s National Military Command Center, among others. At the end of the file was a terse note: “Good searching.”

The released files hooked Mathew and gave him a list of network access points. Rather than a late-night hobby, the computer took over his life. He skipped meals. He barely slept. He used the handle Kuji as he entered secure telecommunications and skipped around through cyberspace looking for an entrance into government secrets. Mathew would first gain access to a system through blueboxing– playing various tones that mimicked those of a phone keypad–which enabled him to grab encrypted password files. He fed those into a code-cracking program and then could go through user files and folders, one by one. One trick he used was to grab someone on the periphery–say, a university professor who was given access to military projects. Mathew knew those users often recycled the same password for various accounts and networks, which enabled him access to more sensitive material. Once inside, Mathew could hack higher and higher, all the way up to the system administrator–giving him complete network control.

The truth seemed to be out there, and just maybe Mathew Bevan, or at least this fearless double of himself in the hacking world, was the one who could finally find it.

Kuji moved stealthily, a mix of Theseus navigating a digital labyrinth and a master burglar, silent, craftsmanlike. Weaving through a labyrinth of electronic pathways, Rome Labs in central New York became the entry point for the nameless, faceless Kuji to access the Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Labs facility, Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, Hanscom Air Force Base in Massachusetts, and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab in California. He hacked into the NATO headquarters in Belgium and the Wright-Patterson Air Force base. Kuji accessed those computers via the system administrator— who, rather unbelievably, did not have a password.

Court documents reveal that one of the first computers at Rome Labs that was attacked was being used by Christopher Mayer. An automatic password sniffing program, which intercepted password-related data, had extracted Mayer’s computer password as “Carmen”—which Scotland Yard later confirmed was the name of Mayer’s pet ferret.

Mayer, 25, had joined Rome Labs a year earlier, following a stint in the Air Force ROTC at Texas A&M. A skilled young analyst and engineer, Mayer was quickly tasked with high-level responsibilities.

Foremost among them was his work on the Theater Battle Management Core System (TBMCS), a significant Air Force restructuring that enabled “the air commander with the means to plan, direct, and control all theater air operations in support of command objectives and to coordinate with ground and maritime elements engaged in the same operation,” and Force Level Execution (FLEX) software.

FLEX was an incredibly dynamic and vital warfare project. According to the Air Force, the program would “provide advanced automation support” for Combat Operations Division personnel to “coordinate, integrate, and control current theater air operations” by monitoring missions, alerting “duty officers and combat operations of potential problems during execution,” and ultimately to “automatically generate replanning options to fix problems.”

Five days of hacking passed before the operatives at Rome Labs even discovered an intrusion. Jim Christy, 42, then director of Computer Crime Investigations (CCI) for the Air Force Office of Special Investigations, would later testify in a Senate Committee on Government Affairs hearing on Security in Cyberspace that “user’s email were read, copied and deleted. Sensitive unclassified battlefield simulation program data was read and copied.”

Rome Labs, a nexus of sorts with other military systems, served as the jumping-off point to launch breaches of other networks, including the defense contractor Lockheed Martin. Kuji was not the only intruder into the systems at that time. Another handle of an unknown user showed up as Datastream Cowboy. In cyberspace, hackers often followed each other’s pathways without specifically coordinating in advance, sharing entry points and tactics as they went, becoming impromptu tag-teamers. The operatives at Rome Labs had no way of knowing what hackers were after–they certainly could not guess that Mathew Bevan, as Kuji, wanted to know about little green men.

The uncertainty about intentions was never more alarming than when an entry point opened up to the Korean Atomic Research Institute. Some files were picked up from there and, shockingly, moved onto the Rome Labs systems.

It was a hack of dizzying proportions and of dangerous international consequences. At a time when diplomatic relations were already strained, America braced for violent escalation with North Korea for several nail-biting hours. Then Kuji appeared to take control of the FLEX system, which for all the United States government knew, could lead directly to war, arguably equivalent to a virtual nuclear button. As one account of the system indicated, access to FLEX gave a user the “power to launch a Peacekeeper missile, with a nuclear payload of 150 kilotons, many times the kill capacity of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945… The missile guarantees total devastation within 20 miles of impact and could have wiped out any major city within a 12,000-mile radius of the launch site.”

It was not merely a computer network, not even just the United States, but the world that faced an existential threat.

In breaching the Wright Patterson Air Force Base systems, Mathew chased the Holy Grail of UFO information discussed by PHREAK. Relevant files could be anywhere in the military’s computer systems, but so were plenty of tedious, repetitive and irrelevant ones. He perked up at a file that indicated details of an apparent anti-gravity propulsion system, a manipulation of gravity considered scientifically impossible by conventional wisdom but reportedly pursued in top-secret work.

As Mathew read through the files with interest, the gravity experimentation seemed connected with a mysterious craft held at Wright Patterson, which he concluded was part of Hangar 18, a legendary secret warehouse where supposedly the Air Force stored and analyzed alien craft.

As another hacker described it, the momentum of experiences such as Mathew’s build upon “the adrenaline, the knowledge, the having what you’re not supposed to have.”

In jumping in and out of files, Mathew realized how much powerful access he had gained in which he had no interest. “I had control of the weapons. I could have been Saddam Hussein or the IRA.”

But, of course, he wasn’t Saddam or the IRA, so he put aside the thought and enjoyed the hidden gems in front of him.

Investigators scrambled as the hacking frenzy ramped up. On March 28, 1994, two separate response teams were deployed to Rome Labs. Truly*Adventurous spoke with members of both teams for this story.

First to arrive at Rome Labs was the team from the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI), sent by CCI Director Jim Christy. His directive was clear: “Gather as much information as you can, and then go brief the [Rome Labs] commander.” Christy told his agents that it would be the Rome Labs commander’s decision as to whether they would secure the entire network from outside intrusions, or if they would leave part of it open to “trace the hackers back.”

With brown hair and glasses and the frame of a hockey player (he’d been a hockey referee until a shot to the face resulted in an eye implant), Christy could take a hard stance that was the result of working previous high-profile cases, including the infamous 1986 case of German students who hacked into American military computers with hopes of selling the secrets to the KGB (recounted in the memoir The Cuckoo’s Egg by Cliff Stoll).

Greg Dominguez

Christy chose Greg Dominguez to be his team leader on the ground. Dominguez and his agents huddled with the Rome system administrator and reviewed the logs from the past week. They began to question witnesses while reporting back to Christy. Dominguez was a veteran special agent for AFOSI. He points to a defining moment in his career choice when he watched an investigator splice back together 5 and ¼ floppy disks cut up with pruning shears. “I was standing over the guy’s shoulder,” Dominguez recalls, “when he pulled up a paragraph of a letter that the suspect had written to have his wife murdered, and I’m like, I’ve got to do this!” Dominguez became a computer crime investigator the year before Mathew Bevan hacked into Rome Labs.

The information Dominguez and his team gathered seemed to confirm the worst scenario, as feared by high-level Air Force officials: a foreign enemy viewing and stealing sensitive files while using Rome Labs as a staging ground to launch a cyberattack worldwide. “When you see people doing searches for particular things, and you don’t know where they are,” Dominguez said, “it’s very disconcerting.”

Dominguez and his agents were in the front office of Rome Labs, waiting to confer with the base commander, when a second investigative team arrived from the Air Force Information Warfare Center (AFIWC). “Neither one knew that the other was going to be there,” Christy recalled. The two groups postured.

AFIWC said they were directed to “track the hackers back,” but AFOSI countered: “That’s not your job.” Instead, their job was “to secure the network.” The AFIWC investigators were based out of Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. Team leader Kevin Ziese brought investigators Scott Waddell, Christina Roth, and Andrew Balinsky along.

Before either group met with the Rome Labs commander, AFOSI reported back to Christy about the scrum of investigators. “You work together as a team,” Christy told them. “Everybody needs to stay in their lane. Our job is to investigate. Their job is to secure the network for the commander.” Leadership agreed to leave a network open to monitor the hackers’ next step.

The two teams set up in a windowless room on the base to monitor the intrusions and collect evidence. Dominguez recalled that somebody had to be present at all times “because we couldn’t trust that we could lock that room up and prevent unauthorized access.” The teams spread sleeping bags under the tables and slept there, taking turns watching the monitors flicker when access occurred. It was tiring and tedious work, and they couldn’t be awake around the clock. But they also needed to catch the hacking in real-time.

That was when Harvard-trained computer scientist Andrew Balinsky and his team devised a practical solution. They recorded themselves saying, “intruder alert.” Then when a network was breached, the sound would play, shaking them from exhaustion and enabling them to run scripts and observe the intrusion.

Previously unreleased court records reveal the labyrinthine process used to stymie tracing of the source of hacking. One exhibit from the Metropolitan Police reveals blue box calls to Bogota, Colombia, which then routed to Cyberspace, a Seattle-based “free, public facility” that “provided a port of entry to the Internet for those without their own direct connection.”

The AFIWC team created their own accounts on Cyberspace to monitor the intrusions’ origin. (According to court records, the accounts were the named “dudeguy” and “nudeguy.”).

While alternating tactics, tensions boiled over between the teams. According to Christy, Zeise and the other AFIWC had drafted a hackback program on the flight up from San Antonio. AFOSI agents informed them it would be illegal. That was when boisterous arguments erupted over whether what they were trying to do was any different from unlawful hacking, and who would have to authorize that, leading to the AFOSI agent flashing his gun and threatening arrest.

The teams ultimately backed off from each other. But they remained mutually suspicious, and their collaborations, although necessary, continued to be guarded. Finally, the Department of Justice, the FBI, Rome Labs, and the Air Force teams joined a conference call to hash out conflicts. They decided to allow one hack back, monitored by the AFOSI agents.

In only a few days, over 30 systems at Rome Labs had been compromised by seven different sniffer programs. As Christy noted in Senate testimony, because hacking occurred through internet providers via telephone lines in Seattle and New York, “what we would have had to do as investigators is go to these local jurisdictions and get court orders for trap and traces [law enforcement methods to identify phone and electronic signals]. With the real-time nature of these cases that really wasn’t feasible.” Dominguez recalled that Scott Charney, then head of the computer crime unit at the Department of Justice, summed up the problem when it came to using online access to justify subpoenas: “Greg, the Constitution of the United States of America is not ready for that yet.”

This was complicated by the fact that clues pointed to an unexpected origin point for the hacking: the United Kingdom.

Scotland Yard had their man. They were ready to execute their search warrant. They circled the house with their cars, driving up and back—waiting for the hacker’s next breach of the United States military so they could go in.

The tide had turned when an informant revealed that they had communicated with a British teenager who bragged about breaking into military sites due to their poor security. The AFOSI contacted the Computer Crime Unit (CCU) of the Metropolitan Police. It proved to be an essential step in the case. The CCU’s local investigations pointed them to a likely suspect, but the next step demonstrated one of the many unique elements of this case. All principals interviewed for this story stressed that this case was a seminal, groundbreaking event in the history of cyberattacks and occurred at a time when analog ways of policing confronted the digital realities of the coming new millennium. Hackers lived and breathed online while the investigators existed in the actual, physical world. For that reason, the Air Force relied on CCU and informants on the ground to undertake old-school pounding the pavement not only to track down the hacker, but to catch him in the act.

CCU recruited British Telecom. A technician installed a call logger on the suspect’s phone. Although a logger cannot record the content of conversations, it logs numbers called, duration of calls, and “certain, unexpected signals”—including the blue boxing techniques used for hacking. The Air Force continued to monitor intrusions while British Telecom collected call data. All parties were confident they had their hacker— but they needed to actually see him do it.

On May 12, 1994, Scotland Yard did precisely that.

“What you had to do was to prove the line,” Mark Morris, a detective in Scotland Yard’s computer crime unit, told Truly*Adventurous. Sometimes that meant breaking down the door so that “you could actually grab the handset, and then you could speak to a BT guy on the other end of the line.” Voice-to-voice confirmation was much better than an electronic record.

In an interview for the story, Morris stressed that this type of direct record was essential to hacking and computer crime investigations. He said that “trying to get judges and juries to understand the complex computer evidence at that time was not easy.”

At 8pm in front of the house where with the teenaged suspect inside, one Scotland Yard officer pretended to be a courier. He knocked on the door, which the teen’s father opened. Then the other Scotland Yard officers entered the home. They “crept upstairs” to find the suspect in his attic bedroom. “We actually literally lifted his hands off the keyboard,” Morris said. “I’ve never, ever seen anyone so shocked.”

The teenager crumbled to the floor and wept.

But it wasn’t Mathew Bevan, aka Kuji. It was Richard Pryce, 16, the young man behind the handle Datastream Cowboy, the other hacker who had been entering protected United States cyberspace at the same time as Mathew. Richard was arguably a more prolific hacker than Mathew, while Kuji had appeared to be the more skilled one, with his trail and example followed by Datastream Cowboy into the top secret systems.

The Pryces, Richard’s middle-class musician parents, stood back in shock.

Meanwhile, Kuji, still an unknown entity, remained in the wind.

To cease hacking was like a superhero boxing up tights and a cape, suddenly going from leaping across rooftops to sitting in a cubicle and looking like everyone else. Mathew’s version of this was to take a steady job in the computer department of the Cardiff, Wales office of Admiral Insurance, the computer now only used for mundane data entry and memos. After the whirlwind of being Kuji in cyberspace, it was a return to the rules of gravity that real life tended to impose.

The work could get repetitive, but he was a good employee, and he needed stability as his life moved in a new direction. Lisa, with whom he had found such chemistry online, had emigrated to Wales so they could marry. He no longer felt the need to engage in hacking or to be driven by obsessive quests for secrets–as though a hole had been filled, a real connection made. Studies of hackers point to a desire to overcome a feeling of helplessness by gaining knowledge and information that was or seemed to be hidden. Accessing those secret files, however fleeting an experience, gave Mathew that needed reassurance that his own life did not have to feel like it was out of reach or under someone else’s thumb.

Mathew heard how the other hacker, Richard Pryce, had wept when arrested in London. Richard, too, as it turned out, had been after UFO information and had been a contributor to the e-zine that had inspired Mathew. Richard’s story had been plastered across newspapers and on television in the UK and beyond. But none of it seemed to apply to Mathew now, especially as time passed.

All the while, Scotland Yard’s investigation turned to a new phase: to find the other hacker. Mark Morris, the computer crimes investigator, was sent to the United States to collect evidence from the various hacked sites. He met with Jim Hansen, an AFOSI special agent, who escorted him across the country, from NASA facilities to Lockheed Martin, from Washington DC to Texas, and to Rome Labs. He was essentially taking a tour in the real world of the cyberspaces that Mathew had hopscotched. Based on the peculiar and novel nature of the hacking case, Morris was given unprecedented access to military facilities. “I remember one Air Force Base, we went down and down and down in an elevator, down into the bowels of what looked like an aircraft hangar. But obviously went a lot deeper. And then down a very, very long corridor, there’s a little room with a couple of guys in there and a couple of servers. And that was the server that had been attacked.”

Morris collected statements and copied logs, all under the watchful eyes of AFOSI agents. “Careers are built on these investigations,” Morris said. He was struck by the “amount of work and worry” about the case—it was a serious intrusion that had rattled the Americans, and Pryce’s arrest was just a part of its resolution.

Though intrusions had stopped, the Americans worried that the unknown Kuji could start at any moment and move from mischief to terror. Morris summed up the thinking at the time: “Pryce is this kid in London, we can’t find anything really deep on him. Maybe Kuji was a foreign actor.”

Even Kuji’s handle was mysterious, with investigators spending time wondering about its origin—was it a symbol, maybe a reference to Asian culture? Andrew Balinsky, one of the AFIWC investigators, later pointed out a more obvious explanation. “It’s just the keyboard,” he said. “It’s quick and easy.” During our interview for this story, he typed out the four letters next to each other.

Morris’ investigative process was exhausting and slow, polar opposite to the lightning fast breaches that had made Morris’ work necessary—transatlantic flights. Endless interviews. And then “you wait months and months and months and months, and then the CPS [Crown Prosecution Service] coming back with a load of questions.” Weeks turned into years.

In 1996, the case was featured in United States Senate hearings chaired by longtime Georgia senator Sam Nunn. On May 22, 1996, Jim Christy, director of Computer Crime Investigations, stressed that the Rome Labs case remained unsolved, and the scope of damages and stolen files was unclear. “These cases will be solved the old-fashioned way. By human intelligence… No one knows where Kuji is. That is still an open investigation.” The publicity from Senate hearings caused renewed concern, and fingers pointed at Scotland Yard. “There was always the pressure on to find Kuji,” Morris said. “We don’t like leaving jobs half done.”

Previous leads on Kuji were dead ends. But one weekend, Morris sat at his dining room table with his laptop. For what must have seemed like the hundredth time, he went through a forensic image of Richard Pryce’s seized hard drive. “Hidden inside a system file,” Morris said, “within a load of empty gobbledygook file of code,” was a “UK landline phone number,” which Richard Pryce would have grabbed from one of the bulletin boards that allowed users to communicate. It was Kuji’s phone number.

Weeks later, Mathew received a call at work from a friend in whom he had confided about his past hacking activities.

“Mat, get to your fax machine. I’m just sending you something,” his friend said.

Mathew waited as the machine churned out page after page of a transcript: testimony before the Senate of the United States. The statement was titled “Information Security: Computer Attacks at Department of Defense Pose Increasing Risks.” The central example of the testimony was the hacking of computers at Rome Laboratories in New York during April 1994. One of the hackers had been arrested, but the other, who went by the handle “Kuji,” “was never caught.”

“Are you scared?” Mathew’s friend asked. “Are you worried?”

He scanned the transcript. During the attacks, the hackers stole sensitive air-tasking order research data...the orders provide information on air battle tactics.

No one knows what happened to the data stolen from Rome Lab.

“They’re not going to find me,” Mathew said, as though willing the idea into existence.

There was another choice besides relying on hope. He could run. He had already outsmarted an array of some of the most brilliant people who worked for massive agencies of the United States government and had slipped right into the braintrust of America, Harvard. He could use the same skills to disappear, to leave no trace in records, to plant misdirection out into the world about his whereabouts and his identity. Airlines, passport systems, bank accounts, nothing would be off limits to a master hacker. Others in the hacking world had become fugitives, such as Justin Tanner Petersen, who had gone on the lam three years earlier from a federal courthouse in California, hacking into a lending company in order to wire $150,000 from their accounts into a bank for his expenses.

But Mathew had a good job, a new marriage, and a life he built, all of which had come somehow from his computer skills. He would not let it pull him down into the shadows, to be resigned to be invisible again.

One summer day, Mathew got a call from one of the insurance firm’s finance directors. He was requested to come upstairs to check the managing director’s computer. When Mathew opened the door to the director’s office, he saw eight or nine men in black suits. He didn’t recognize any of them. A man held out his hand.

“Mathew Bevan?” Mathew reached out and shook the man’s hand.

“We’re placing you under arrest for the suspected hacking of NATO, NASA, and various Air Force bases across the world.”

The men in suits were from SO6, or Special Operations 6, the Computer Crime Unit of Scotland Yard. They escorted him out of the office and placed him in a cell. They threatened they would arrest his wife Lisa, while he protested that she knew nothing about hacking. They would only agree to leave Lisa alone if he cooperated.

After spending more than two days in a cell, investigators brought him to his small flat on the top floor, corner at 145 Penarth Road. Lisa, 24, answered the door, confused. “She was quite ill at the time,” Mathew would recall. The shock of seeing her husband escorted by shadowy police rattled her.

Despite her frail health, Lisa was “absolutely going ballistic.” She demanded an explanation while the officers collected evidence from Mathew’s computers. They even took down his X-Files posters and grabbed his videos of the show.

“Is he hacking from his job?” Lisa asked the police. The officers kept her separated from her husband, and refused to answer her questions.

Mathew was left to his own recognizance and with one of the biggest challenges of his life, even while the United States military and Scotland Yard aligned against him: could he convince his wife he wasn’t some bad guy?

The phone calls did not help. Lisa would answer some of them.

“Is Mat there?”

“No,” she said, although he was.

“That’s okay, we know he’s there,” the voice responded.

Other callers would say, “Yeah, we will speak to him,” certain that he was in the room with her.

Lisa told Mathew that the calls were full of noises, like “radios, a communications facility.”

Mathew’s setup where the hacking started.

Then the threats started. One caller told Lisa: “I wouldn’t be surprised if Mathew was found with a bullet in the back of his head.” The calls were untraceable, but Mathew believed they could be foreign government operatives sizing him up, or possibly rogue groups after government secrets who wanted to break him down into revealing what he found.

After that, the Bevans moved to a safehouse and took on assumed names. “The press didn’t know where I was; nobody knew where I was.” There were nice aspects about it. The safehouse had a garden where he decompressed.

Still, the calls continued. Some callers remained anonymous. Others claimed to be working for foreign governments. Mathew would change his number, but the calls would always start again.

Once, he answered the phone himself. “Fuck off,” he told the caller. Mathew said he was having his phone number changed.

“I know,” the caller responded. He proceeded to say Mathew’s new phone number—which he wouldn’t receive for a few more days.

Concerned about his safety, officials moved him to a new location and named him “Mr. Smith.” In a different way than his hacking handle, his identity was being stripped away. He had to focus on what he could control. Although his police officer father was unnerved by his purported crimes, he wanted to protect his son. He helped Mathew acquire representation by Simon Evenden, a Cardiff solicitor.

But much of Mathew’s prospects pivoted on ongoing developments with Richard Pryce, the other hacker to have entered the government systems at the same time as Mathew, whose case became a kind of test. Richard, with a boyish grin and light brown hair parted in the center, had been a talented double bass player at the prestigious Purcell School in Harrow, Middlesex, England, when he got into computers. His parents, Nick and Alison Pryce, were stringed instrument dealers and restorers and mainstays of the city art community. Their London shop was full of violins, cellos, violas, and basses. His sisters were also musicians.

PHRACK Magazine.

With his growing fascination with computers, Richard threw himself into the world of online bulletin boards. Richard saw hacking as “a game, a challenge.” His handle, Datastream Cowboy, was a jaunty, cocky name that befitted Richard’s youthful ambition. The high schooler contributed a post in the same issue of PHRACK ezine that had caught Mathew’s attention. Richard, meanwhile, was intrigued by the other post that had fascinated Mathew. “I read that UFO material was being kept at Wright Patterson base,” Richard would later say, “and I thought it would also be a laugh to get in there.”

After Richard’s arrest, Scotland Yard, working with civilian computer experts from Queen Mary College, seized the young musician’s “computers, floppy disks, notebooks, notes and other material.” They quickly realized he was no spy or foreign agent.

“On the one hand, you’ve got a young kid in his bedroom, who is looking for UFO material and trying to find stuff about weapons or armies or what have you, and he really is a nice lad in every other respect,” Morris said. “And then you’ve got teams of people on the other side of the world, literally pulling their hair out with a major attack on their system.”

Richard admitted to the police that he had performed the hacks. He “also indicated explicitly that he was aware that his accesses were unauthorized and wrong.” His notes documented the specific systems he hacked at Rome Labs and elsewhere. According to records of the case, he “had in his possession files which appear to be identical or very similar to some of those that were on some of the USAF and other computers attacked.” He had “lists of legitimate account holders” at the bases and “their associated passwords.”

Richard’s family scrambled to find local solicitors who might take on the case, all of whom “completely freaked out.” The stakes were too high, the case so complicated, and lined up against them were Scotland Yard and the United States of America. In a last-ditch attempt, they wrote to a well-known judge, who referred them to a firm that listened to their pleas. “One of the slightly more junior lawyers knew me,” Peter Sommer said. Armed with a law degree from Oxford, Sommer was a former deputy editorial director for a London book publisher turned computer security consultant. Sommer soon became an expert witness for Richard’s defense, all while the alleged transgressions of Mathew, aka Kuji, were bundled together with Richard’s by investigators.

In 1985, Sommer had published The Hacker’s Handbook under the pseudonym Hugo Cornwall. The limited print run book was unintentionally buoyed by no less than Scotland Yard. Officials there acquired an early copy of the book and were reportedly “dismayed” by the book’s contents, which the London press described as “basic step-by-step guidance on how to break into databases, read copy, and delete or corrupt information stored there.” Sommer had written that “hacking is a recreational and educational sport.”

Sommer began examining the Crown’s case against Richard, hypothesizing their legal approach, and then analyzing its efficacy. His report demonstrated a paradox: the case against the teenagers was both substantial and highly flawed. The framing of Kuji and Datastream Cowboy as dangerous hackers was “a round of budget-bidding aimed at the US authorities.” Sommer noted that AFIWC lead investigator Kevin Ziese, “in particular, has appeared at a number of US computer security conferences.” (Elsewhere, Christy noted that Ziese implied at conferences and events that his ACIWC was the pivotal group in solving the case, furthering the rivalry on display at Rome Labs.) Richard had “no master plan.” He was a seeker and a collector; “a 16-year-old exploring the world in ways which might be irresponsible and foolish but little more.”

Sommer argued the prosecution cherry-picked items “and have seen in them a relevance and significance which had eluded RP himself.” He asserted that Richard had “actually quite limited” computer skills and knowledge, and that the young man inaccurately described the hacks to which he had allegedly confessed participation. He was clearly intelligent and obsessed with hacking, but “not omnipotent and certainly not a genius.” He used well-known hacking tactics. He grabbed all the files he could, with little focus. Thankfully, the fraught hack into Korean systems turned out to relate to South Korea. As Jim Christy would later testify, if the hackers had stolen North Korea’s secrets and dropped them at Rome Labs, “it would have looked like the Air Force was attacking them.”

Sommer pointed out an attempt by investigators to trumpet the idea of a collaboration between Kuji and Datastream Cowboy based on their simultaneous hacking. While hackers could piggyback on each other and share information in fleeting online chats, the two British teens had never met in person or spoken on the phone. Sommer—in many ways, the authority on this subject—argued in his report that hacker collaboration was usually a misnomer. To call hackers a group “implies a coherence which is not really there.”

Sommer shared his analysis and information on the case with Simon Evenden, Mathew’s solicitor. Evenden suspected that the Air Force was in a bind by the very nature of the sensitive hacking. The officials were unable to reveal the actual secret documents, meaning that they had to resort to very ineffective descriptions of documents. Because of the transatlantic nature of the hacking, Evenden knew that “it would have cost hundreds of thousands of pounds to bring witnesses over from the US.” The defense could compel a litany of Air Force investigators to travel to the United Kingdom, racking up bills, and could subject them to withering cross-examination, which could include the details of their inter-department squabbles during the response to the hacking.

On March 21, 1997, Richard Pryce changed his plea to guilty. He paid a £1,200 fine (£100 for each offense). In the aftermath, charges against Mathew were modified, with a focus on his alleged placement of sniffer programs at Rome Labs and Lockheed. By November 21, 1997, at the Woolwich Crown Court, prosecutor Andrew Mitchell said that a trial for Mathew was “no longer in the public interest.” He pointed to the Richard Pryce case: “The court’s hands are tied as to sentence, and the role of this defendant was secondary to that of another who was dealt by a fine.” In response, the Crown Prosecution Service offered “no evidence.” In other words, prosecuting such a technically difficult case, even after investigators raced against the start of a possible world war, was hardly worth the trouble. The case was closed.

Mathew Bevan exited the courthouse a free man wearing a black suit and dark sunglasses, which had become a trademark look as he was pushed into the spotlight, a kind of armor against public scrutiny and distrust.

The weight of the world lifted from his shoulders, Mathew could reflect with a mixture of relief and bitterness about his perception of him. “I’m not a malicious person. My motives were never to sell information,” he pointed out. “I could have downed as many computer systems as I wanted.” As for the UFO-related files he had been looking for, he had read them without even downloading them.

Mathew Bevan

Back in the United States, in a speech that year, Paul Rodgers, who led the President’s Commission on Critical Infrastructure Protection, described the new age of cyberwarfare: “In the past, armies had to march, navies had to sail and air forces had to fly for great damage to be done. Today, we live in an age where the ability to induce terror comes in miniature. We are now engaged in a war that will never end.” He said the Rome Labs Case “lends credence to such movies as WarGames where a teenage hacker breaks into a defense computer and creates great mischief.” The ultimate threat did not rest with Mathew Bevan or Richard Pryce, whom government narratives turned into “master spies,” but with lax security. Most involved in the case seemed to agree, explicitly or not, that the hackers who “nearly started a third world war” had done a service by revealing weaknesses.

The Rome Labs case laid the groundwork needed for the coming digital era: how evidence would be collected and maintained, who would respond to attacks and how they would monitor and contain threats, and perhaps most importantly, how hackers would be held accountable. The response was used to increase funding and prioritize cybercrime prevention and response. On July 15, 1996, President Clinton signed Executive Order 13010, Critical Infrastructure Protection, establishing organizations “responsible for analyzing cyber and physical threats… [to] national infrastructures,” which included government services. The President’s National Security Telecommunications Advisory Committee published an extensive report in December 1997 calling for further funding and sweeping changes. That committee is now chaired by Scott Charney, who had cautioned AFOSI agents during the Rome Labs incidents about the then-limits of their cybercrime investigative powers.

Richard Pryce stepped out of the computing limelight once his case was resolved. He attended the Royal College of Music in London as a scholarship student and was awarded the Eugene Croft Solo Double-Bass Prize. He would go on to perform internationally with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra, and the English National Opera, and still records with artists including Sam Smith and Kanye West.

Mathew seemed to spend more time than his counterpart processing the events, and arguably had a harder time removing himself from their aftereffects. He blasted the Air Force’s more extravagant claims as “propaganda.” He claimed that he was never a threat, and that the Air Force’s severe response to his intrusions was an outsized reaction of embarrassment. He also felt members of the CIA, FBI, NSA and other agencies continued to keep tabs on him after the case was dismissed, which was later unwittingly confirmed by Jim Christy, the computer crimes investigator. At other times, Mathew admitted to the appeal of hacking glory, which came with another paradox. He acknowledged he wished “to be the best hacker. But it is challenging—the problem is that hackers always want to be recognized, but the only way to get real recognition is to get caught.”

Christy became a regular speaker at DEF CON, an annual hacker convention. In the early 2000s, Christy recalls a hacker coming up to him and presenting him with a “present from Kuji for you.” Christy held up the shirt. Mathew’s autographed photo was on the front. On the back read: “Kuji’s World Tour 1994. Special thanks to Special Agent Jim Christy and Kevin Zeise.”

In the years following his acquittal, Mathew had a stint at Nintendo in marketing and worked as a security consultant for several companies. At one point, he started his own company, Kuji Associates, which tested the ability to breach clients’ networks. Part of the service provided was to demonstrate a “hackers’ psyche.” Mathew’s post-case bravado sometimes lapsed into sadness, particularly for the effects on his family life. He lamented that the case and its fallout “has been a bit unfair on my old man, he has had a bit of pressure from people. The fact is I think... I’m not sure what I think.” He feared that traveling to America to meet his wife’s family might result in his arrest from American investigators who felt they had unfinished business.

Looking back over Mathew’s court proceedings after the Rome Labs hacking, it was notable that the Wright Patterson breach was left out of the charges against him, leading some observers to believe the United States government did not want to acknowledge details about UFOs in court. In the years since, the United States have released several large batches of previously highly classified information about UFO claims and encounters–and continue to do so– which have led to a variety of interpretations and discussions but certainly implicitly acknowledge the government knowing more than what had been previously public.

Mathew Bevan’s hacking journey represented both a coming-of-age story and a love story. After a childhood spent struggling to fit in, the confidence he gained on his keyboard allowed him to learn to connect with others, including his future wife, who in turn dared to pick up and move to another country as they pursued a relationship that began through chat rooms and persisted through the stresses of investigations and charges, as well as her illness. Several years after the case was resolved, Lisa died of cancer, leaving Mathew devastated and picking up the pieces with maturity and self-awareness that had come through his trials, literal and otherwise.

Their online, external and speculative worlds intersected a few years before her passing. With the case against him behind them, and with hopes for a brighter future, Mathew and Lisa vacationed in Fuerteventura in the Canary Islands. Looking up, they saw unusual lights up in the sky that changed color, flickering on and off. They watched for hours, without any government secrets or hacked files telling them what they saw, a stretch of beauty and wonder that belonged only to them.

NICK RIPATRAZONE has written for Rolling Stone, GQ, Esquire, The Atlantic, and is the Cultural Editor for Image.

For all rights inquiries, email team@trulyadventure.us.